Czech national space in the second half of the 19th century

One of the premises for a nation’s existence is identification of individuals with its particular form, referred to in articles, speeches, poems, songs, pictures and other means of expression. According to writer Elias Canetti, identification of individuals with a nation is connected with their acceptance of a mass symbol or symbols. It is important, therefore, that for many national movements in the 19th century the mass symbol became space: land, homeland, or perhaps a concrete location or area related to national mythology, a place which constituted ‘national space’. According to Czech historian Miroslav Hroch,[1] a tangible cultural need of certain communities at the time was self-projection through real space.

That observation is particularly true of the Czech national movement throughout the 19th century. In many Czech minds, the territory of Czechia acquired an elevated stature as a national land, and was always expressed through different, often poetic, means. A perfect example of this are the lyrics of the Czech national anthem, in which the singer asks, ‘Where is my home?’, only to pass on to describe its indeed idyllic appearance with water murmuring across meadows, with hillocks covered with broadleaf and fir woods or fertile orchards. In this way, descriptions of the Czech landscape reflected the emotions and feelings of the patriots. Writer Václav Štech confirmed the existence of that form of idealisation at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries when he wrote in his work, tellingly titled National Catechism, ‘our homeland is a beautiful land. Some places can easily rival picturesque locations abroad […]. Our homeland is a fertile land. The Czech people have toiled to raise the fertility of their land to such a level that this land of ours occupies the most prominent position’.

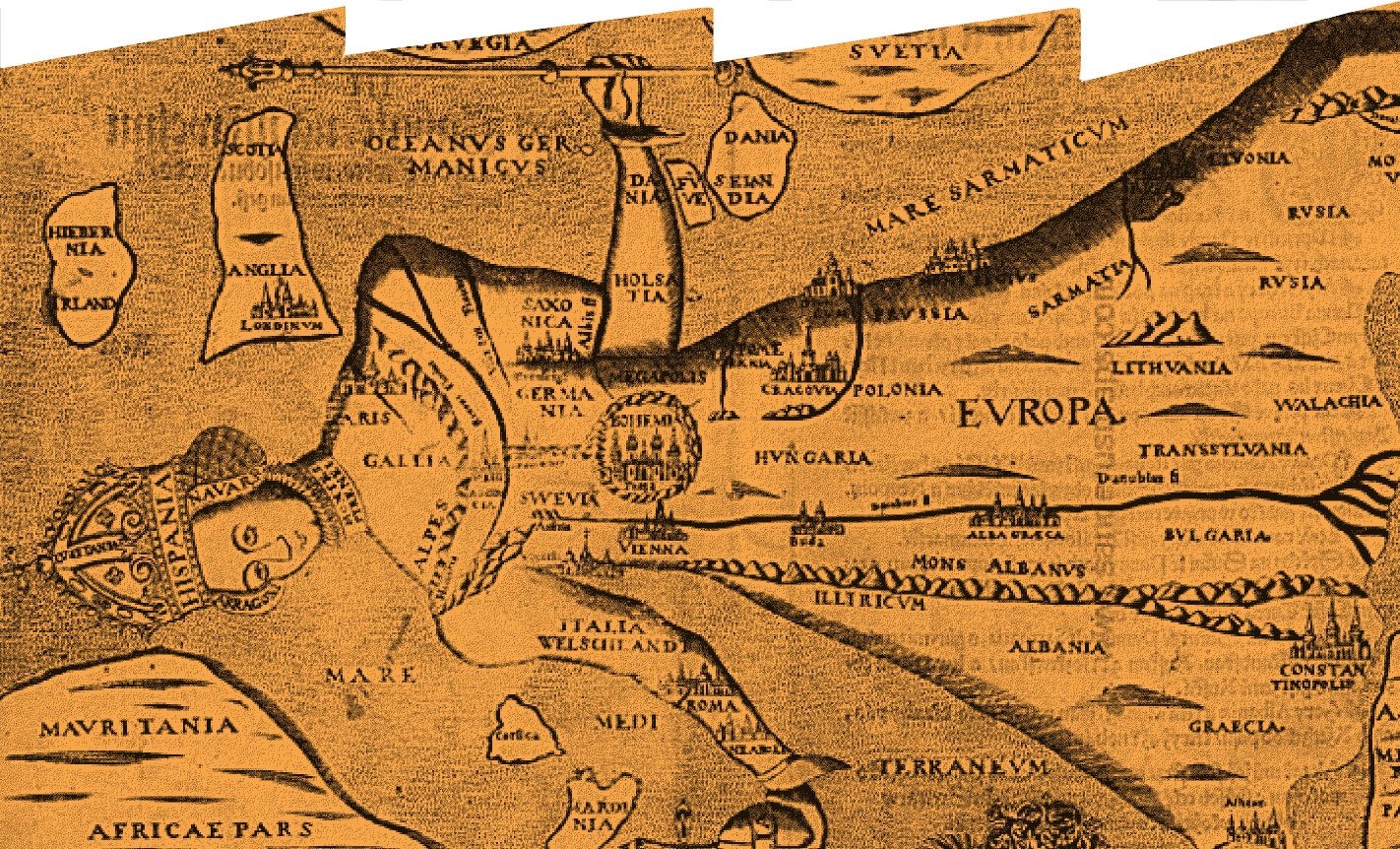

As to the Czech people’s interest in their own space, which, in the words of the anthem, is ‘Paradise on Earth to see!’, it had no small influence on them that Czech lands occupied a supposedly privileged position in the heart of Europe. The avowed central position of the Czech nation was of considerable value to the 19th century Czech patriots. In their views, they relied on the concept of the middle, elaborated by German thinker Johann Gottfried Herder. His philosophical theses include the terms ‘the golden middle’ or ‘the happy fate of middleness’. To Herder, the middle and being in the middle were positive values, which excluded all extremes. They represented permanence, stability etc. As literary scholar Vladimír Macura demonstrated, Herder’s concept of the middle corresponded in many respects to the Czech national movement, whose members were inclined to mythicise their thinking of the world, of the position of the Czech society in it, of its past and future. The alleged central location of the nation and language thus became a quality which embodied the ideal of perfection, the geographical centre, the articulatory position of the tongue in the oral cavity, the stereotype of the Slavs, including Czechs, as people of middle height etc.

It is notable that at the time a similar way of thinking was present among neighbouring Germans, to whom the Czechs had an ambivalent attitude throughout the 19th century. According to the leading 19th century Czech historian and politician František Palacký, facing Germans and skirmishing with them was the most fundamental driving force in Czech history. Due to the central location of their lands, Friedrich Ludwig Jahn, educationalist and representative of the gymnastic movement, marked the Germans out as das alte ehrwürdige Mittelvolk Europas (‘an old, venerable nation in the centre of Europe’).

The 19th century Czech society regarded national space as a fundamental value and a living symbol of the Czech nation. Homeland became a soothing and consoling mother to the steadily developing Czech society, and the very use of the term ‘homeland’ implies that this Central European area was perceived as a natural Czech territory, their property which belonged to them by rights. This belief was sustained by numerous historical myths. One of the most important of these was the tale of founding father Czech and his retainers’ arrival in the land. In his legendary speech on top of the famous Mt Říp, situated between central and northern Czechia, the forefather symbolically handed over the land to his companions. From the contemporary point of view, it is clear that the 19th century Czechs associated the tale not only with the act of settling the geographical area in question but also with the fact that the land was given a name and its settlers received a background. They often derived historical arguments from the tale to support their theses.

Yet the question remains how the ‘Czech national space’ originated and what was behind this ambiguous term at the time that the modern Czech nation and mass national movement were being formed in the 19th century. On the one hand, the issue encompasses the above mentioned idealisation of the whole geographical area, which should ideally be nationally homogenous, i.e. Czech. On the other hand, the subject in question involves the phenomenon of Czechisation of public space in actual localities, communes and towns. In other words, the Czech nation was symbolised and characterised by a concrete – and ideal – landscape and appropriate localities of national importance. In delineating the territory, the border was of fundamental importance. As Miroslav Hroch points out, initially ‘only’ state borders of historical formations underwent qualitative transformations while modern nations were taking shape: they were gradually nationalised.

Beginning from the 19th century, borders were believed to be external and, above all, ‘natural’ boundaries separating respective national communities. Only the citizens who were homogenously unified into a modern nation should live within the perimeter. A vivid example of such a perception of the state-national border was the heroic myth of the borderland town of Domažlic, situated in the west of Czechia and memorable for several notable Czech victories over the invading Germans, which was well-known among the Czech people in the 19th century. For the same reason, considerable importance was attached to the Czech borderland mountains, which were regarded as natural and, most importantly, unclimbable granite defence walls. A testimony to this belief may be found in some poems and songs celebrating the Šumava mountain range and the Czech Forest. As the then stereotypical beliefs had it, the safe Czech plain was inhabited by the peace-loving Czech nation, while outside, across the border there lived the hostile German element. Borderland mountains and thick forests were there to protect the Czech people. Any alteration of the ‘natural’ borders was indeed unthinkable to the modern Czech society of the 19th and 20th centuries. It is well illustrated by the shock that the Czechs experienced in September 1938 when, under the Munich Pact, Czechoslovakia was obliged to yield a vast territory to Germany, which moved the state border well into the republic.

Let us remember, however, that the concept of national unity of the citizens of the part of Europe in question was an illusory idea. Contrary to the fact that the ideal of a nation closed within its ‘traditional’ territory was extremely appealing to the Czechs throughout the 19th century, such visions were incompatible with the reality of the existence of Czech Germans not only on the outskirts of the Czech lands, in the borderlands but also in the very heart of the nation – in Prague. It would not be a gross exaggeration to claim that in the second half of the 19th century there arose and steadily intensified a conflict between the Czechs and the Czech Germans over ‘national space’, among other considerations.

First and foremost, the so-called Grenzlandkampf – struggle over the Czech and German linguistic border and over the land’s national character – began in southern and western districts in Czechia at the beginning of the 1880s. In reaction to the situation in the ‘endangered territories’ Czech national organisations were formed, including local Slav clubs, sections of the National Posumava Association and the National North Bohemian Association. They intended to shake the nation from indifference and, as it was put at the time, to strive to return the territories appropriated by the Germans to their ‘rightful owners’. According to columnist Adolf Srb, ideally a dam should be erected at the borderland between the two nations in order to protect the Czech nation from the ferocious and ruthless surge of the German ocean with its tribal anti-Czech hatred and innate expansionism. The scheme aimed to linguistically Czechise the mixed territories, i.e. the strategy to return them to their ‘rightful owners’, the Czech nation, included the organisation of national celebrations and lectures, support of Czech schooling and Czech tourism, and, last but not least, emphasising the Czech character of communes and their residents by means of road and shop signs in the Czech language, numbering houses, issuing public announcements and decorating public establishments and flats in the national spirit, with busts of Czech personages and paintings depicting scenes from the national history.

‘National space’ did not signify merely a geographical territory in that part of Europe. Its integral constituent was space in various concrete localities, both famous places and individual communes and towns. Against that background, surrounded by the aura of legends and myths, lay Prague, capital of the nascent Czech nation, and hence also of the national movement, the spot where past and future lives of illustrious Czech men and women, their history and culture centred. Prague was a symbol, her streets and squares afforded many opportunities for the Czech society to hold symbolic demonstrations. These events confirmed the prominent position that the city had in the Czech-speaking residents’ minds. These public initiatives included marches to commemorate the deeds of eminent patriots and their anniversaries, for example the celebration of the seventieth birthday of the above mentioned František Palacki in 1868; the celebration of the laying of the foundation stone for the National Theatre also in 1868; funerals of distinguished patriots, for example Jozef Jungmann’s funeral in 1847, which was considered to be the first national demonstration; the unveiling of statues and commemorative plaques. An inevitable part of these enterprises were public speeches, including slogans, declarations, songs or hymns, formulated in the appropriate language, i.e. Czech. With these initiatives the Czech society claimed Prague as their capital, an inherently Czech place, the exponent of the Czech nation. It was in that city that the past mingled with the present, which in turn drew strength from the historic fame of the place to realise the current aspirations of the nation. During many national events Prague was described as a Mekka for the Czechs, the pilgrimage destination for all patriots.

At the same time, the Czech society took full advantage of the alleged Czech character of the city and did not miss any opportunity to remind that to the Czech Germans who were numerous in Prague. The multivolume scientific Otto’s dictionary of 1903 ostentatiously referred to Prague as an unequivocally Czech city which it had been in the Hussites’, clearly anti-German, times.

Similar declarations, which we now view as purposeful and offensive to the Prague Germans and which aimed to present and thus de facto Czechise the Prague space, can be found in speeches made by the city’s official representatives. In this context the address delivered by the newly elected president of the city, Tomáš Černy, at his ceremonial instatement in September 1882, which included references to the city as ‘our ancient, our beloved Slav Prague’, was of more than just the symbolic consequence. It is noteworthy that it was in recognition of that particular speech that Tomáš Černy was granted honorary citizenship as an eminent representative of the city. While his speech was enthusiastically welcomed by the Czech side, the Germans demonstratively left the city council, which remained exclusively in Czech hands since 1888.

It is evident how closely attached members of the 19th century Czech national movement were to the idea of possessing ‘their own’ land. However, that land had to be shared by the Czechs with their German co-citizens, who lived in the atmosphere of steadily increasing tension. The real space, which had acquired the qualities of an idealised realm, and the man-made public space in towns, communes and well-known localities were to the Czech minds an important symbol and tangible proof of their national existence in the multicultural Habsburg monarchy. The end of the first stanza of the Czech national anthem says, ‘And that is the beautiful land, / The Czech land, my home!’

Translated by Anna Mirosławska-Olszewska