Mutual aid

One of the pillars of anarchism is the self-organization of human communities, in its various meanings: as a practice adapted to circumstances, as the spontaneous action of people gathered for various reasons outside the official system, and as a theoretical recipe for how a society should function without the state or other hierarchical structures of power. Theorists of anarchism have paid much attention to cooperation between people. In the classic foundational text Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution (1902), Peter Kropotkin diagnosed solidarity tendencies in the human population that are analogous to examples of cooperation in nature. In opposition to (or in addition to) natural and social Darwinism, which are built on the notions of competition, natural selection, domination, and elimination, Kropotkin points to numerous examples of mutual cooperation and support in the natural world and in human populations – beginning with prehistoric communities, to medieval cities, to the nineteenth-century labour movement.

Mutual aid ideas are continued by mutualism. This current of anarchism owes its name to the principle of mutual benefit existing in nature in the form of cooperation between various species. Mutualism promotes collaboration between independent producers united in associations as part of a fair exchange of goods and services based on favourable agreements regulating mutual relations. This is possible thanks to loans granted by the national bank – a , which is a non-profit institution by definition in this system. Mutualism does not discourage private property as long as it does not lead to exploitation and domination; nor does it promote violent upheaval. It assumes that a community of free associations would gradually, naturally and democratically relinquish the state and central power structures1.

Without denying anarchist persons their fundamental role in building resistance situations and structures, it can be observed that mutual aid and self-organization go beyond the framework of the postulates of the anarchist movement and have been described much more broadly as social mechanisms functioning in the world of people and the world of nature; under favourable conditions, they can ensure the establishment of relations of peaceful cooperation. Thus, anarchism would be possible without anarchists and anarchist doctrines, although it is their determination that furnishes these actions with a more permanent sense and theoretical motivation, and it also allows them to be seen in a context that is broader than the current one.

Anarchitecture

Similar observations apply to the phenomenon called anarchitecture – anarchist architecture. Seemingly, it has little in common with traditionally understood architecture – the most political of the arts – which is cost and energy intensive, requires precise professional knowledge, and is focused on the dominant figures of the Designer (usually male) and the Ordering Party (also male). Modernist architecture in particular – with its associations with the liberal system, the cult of the superior plan, the paternalistic architect and social engineering, in both centralized and authoritarian systems of communist countries – seems to be in opposition to bottom-up, voluntary organization and direct democracy, thanks to which the user becomes the author or co-author of his own living environment. In the search for democratic architecture models, modernism and the tradition of top-down planning have usually been rejected; instead, these pursuits have turned to a different type of construction: to vernacular architecture, which is non-professional and based on local building traditions; to examples of self-made construction in communities functioning outside the mainstream of urban policies – slum districts, favelas, homeless encampments, settlements related to alternative forms of living, homes in allotment gardens or spontaneously created playgrounds for children. Anarchist tendencies have been noticed in projects that assumed the participation of residents – both in the design, and later in various forms of co-management of the already built living environment, including the cooperative movement and the possibility of further free transformation of ready-made housing estates. Activities in the city space can also be anarchic in nature: squatting, urban guerrilla gardening, ephemeral architecture related to the organization of mass protests – all of these serve to undermine the existing power relations. There are many projects in which architects are not involved at all. Some are temporary and ad hoc, while others arise out of grim necessity – not as a result of the conscious choice of the users. They do, however, offer a kind of alternative to centrally managed city designs, whether liberal or socialist.

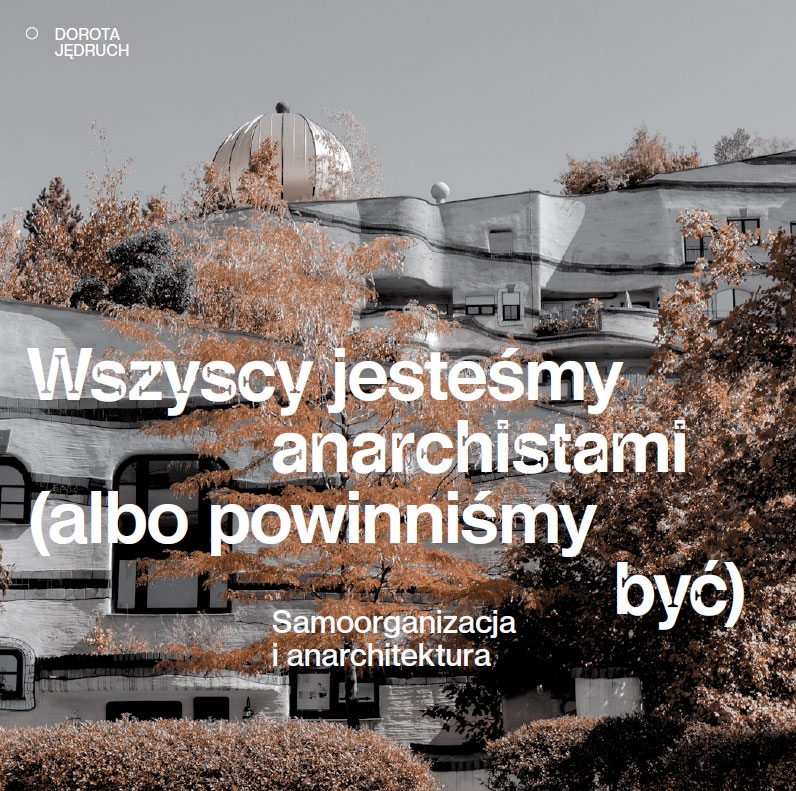

Despite the huge diversity of the circumstances of the creation, motivation, and character of buildings, the forms of anarchitectural projects seem to be surprisingly similar. Polycentric structures dominate. They accumulate layer by layer, they grow organically, they use found materials and recycling; they are striking in their multiplicity of textures, shapes and colours, and with their ingenuity in reusing ready-made objects. Although the creators of anarchist buildings subordinate them to the aesthetics of austerity and randomness, we often end up with carefully decorated objects because anarchitecture also uses the strategies of street art, murals, typography, and the spontaneous and organically growing creativity of the users, both professional artists and amateurs. This participatory logic is rooted in a building model based on a solid skeleton that is designed by an architect and then filled with modular blocks whose functions are subordinated to the needs of the users. It is dominated by a sense of multiplicity that is adequate to the individualism of the inhabitants of the building, with their different tastes and own ways of using the space. Surprisingly, even buildings in whose creation professional architects participated – from the Dadaist Hundertwasser to the minimalist and sophisticated Aravena – are also associated with “architecture without an architect”: colourful, ludic, escaping subordination and constraints, anarchic in their creative freedom, and dropping the rules of dogmatic composition; they are “plurality in plurality”. Arbitrary and unauthorised construction that is considered anarchic has fascinated both modernists (as an archaic model of functionality) and anti-modernists (as liberation from the dogmatics of the modernist plan).

The term “anarchitecture” is believed to have been coined in the 1970s by a group of intermedia artists in New York. These included Laurie Anderson, Tina Girouard, Carol Goodden, Suzanne Harris, Jene Highstein, Bernard Kirschenbaum, Richard Landry, Richard Nonas, and Gordon Matta-Clark. Indeed, they adopted the name The Anarchitecture Group, and in 1974 that was the title of their exhibition. The members of this group always acted anonymously and collectively. They offered a critical commentary on the modernist model of post-war architecture, its inertia and lack of susceptibility to change, as well as its close links with the neoliberal order.

It is difficult to precisely define the meaning of the word “anarchitecture”. In a way, it works like a filter: depending on the intentions, users can screen all sorts of case examples through it. A review of publicists’ opinions shows how multithreaded the understanding of anarchitecture is. In Polish literature, this concept appeared – perhaps for the first time – in 2002. It was used by Rafał Górski in an article for the anarchist magazine “A-tak”2 – a synthetic presentation of examples of buildings constructed with various forms of self-organization and user participation. However, he did not explicitly define these buildings’ relationship with doctrinal anarchism.

Górski remarked that the “anarchitecture” featured in the title of his article was initially a pejorative commentary on the construction of a social centre for medical students called La Mémé3 (the whole investment project consisted of dormitories, restaurants, administrative buildings, a theatre, a chapel with a parsonage, a sports facility, a school, and a kindergarten). It was built according to a design by the office of Lucien and Simone Kroll in the years 1970–1976 at the Catholic University of Louvain in Woluwe-Saint-Lambert, Brussels. The project grew out of criticism of international modernism in the spirit of Team Ten (Kroll was a representative of the group), but also from the mood of the student revolt of 1968. The architect was invited to the project by the student community, which regarded the official plans to redevelop the campus with reluctance; ultimately, the building complex was created in close design cooperation, that is, it was co-designed together with its future users. The Krolls proposed a modular structure based on a type of structural frame into which they freely installed the modules of individual rooms. Responding to the specific needs of individuals, they also coordinated the discussion and selection of solutions. During the preparation of the mock-up model of the entire compound, the participants of the design process

“moved pieces of sponge around. When disagreements broke out or one group became dogmatic and stubborn, Kroll reorganized the team so that everyone could see all the problems until a possible solution emerged. Only then did he draw plans and sections, on the basis of which construction could begin.4

The result of this creative process is a complex of buildings with irregular structures and dancing rhythms of windows and glazing with various sizes and colours of joinery on the façades that are remarkable for their variety of materials, textures and elements used. Critics considered it an illustration of “anarchy” not only in terms of the unusual organization of the design process but also in terms of the ultimate form that had been achieved. The lack of the superior authority of the designer and the replacement of a top-down plan with a process of organic and collective composition led to the creation of a complex of buildings that is devoid of aesthetic “order” but is pluralistic instead.

For his second flagship example of anarchitecture, Górski chose Byker Wall in Newcastle, designed by Ralph Erskine. The implementation of this project lasted from 1969 to 1981. The uniqueness of the task resulted from the belief that it is possible to revitalize a neglected district of the city without getting rid of the local community (typically, such projects assume the resettlement of residents, and the district undergoes gentrification). The design of this housing estate was consulted with future residents (which is usually impossible at the initial stage of the project because future tenants are generally not known at that time). The architect officiated in an abandoned funeral parlour that he shared with a garden centre. This place, where discussions and consultations were held on the emerging project, blended in and became part of the everyday life of the local population. Erskine started by building a small section of the estate to give future users a chance for further consultation based on the existing prototype.

The review of examples of anarchitecture proposed by Górski primarily concerned projects created in the 1960s and 1970s on the wave of cultural changes of 1968. He considered the activities of ARAU (Atelier de Recherche et d’Action Urbaine) in Brussels after 1969; he selected projects related to the counterculture movement (including the well-known hippie settlement known as Drop City, with houses in the shape of geodesic domes) and self-propelled construction using recycled materials: waste and fragments of old boats, welded car bodies, barrels, bottles, tree houses, houses on wheels. He noticed some later examples of cohousing, as well as further experiments in the field of participation: Wohnregal, built in Berlin on the occasion of IBA 1986 (designed by Nylund, Puttfarken and Sturzebecher), and a block of flats in Malmö from 1991 (designed by Ivo Waldhör). In the conclusion of his text, he emphasized being interested in a certain “building philosophy”, the primary goal of which is to save materials and create a community of residents around the construction and further functioning of houses. “What was typical of anarchitecture was the belief that a great wealth of construction and artistic inventions still remains hidden in the creativity of individuals and groups animated by a common thought that this activity has value, that it can contribute to shaping personality”, he explained. For him, anarchitecture was “a verb, an ‘action’, not a set of correct prescriptions and rules. It gains value when it contributes to a direct relationship between the user and the dwelling, and between the home and the natural environment”.5 Unmistakably, in his article Górski included reflections on the form and aesthetics of this type of architecture, and he reconstructed the social circumstances related to the democratic process of its creation and functioning in as much detail as possible.

An even broader range of links between architecture and the anarchist movement was outlined by Jarosław Urbański.6 In his view, anarchist tendencies in relation to planning policy and architecture go hand in hand with a critique of the technocratic modernist city and modernist architecture. Anarchism finds its justification in the fight for the city: in the revision of property relations, criticism of liberal or centralized governance, urban resistance, anti-eviction, grassroots movements, urban guerrilla schemes, self-organization, squatting. In addition to the examples of anarchitecture that appear in Górski’s text (Kroll, Erskine, Wohnregal, Waldhör), Urbański lists Aranya Township at Indore (designed by Balkrishna Doshi, 1982), the works of Walter Segal, the Danish group N55,7 as well as the activity of Pracownia Architektury Żywej (Studio of Living Architecture), run in the 1980s by Andrzej Janusz Korbel. The last example is particularly important as it shows the essential links between anarchism and pro-environmental, ecological ideas. Korbel attracted the attention of the author not only because he implemented ecological ideas, criticized architectural modernism, and remained sceptical about the neoliberal changes of the times of the Polish transformation. Urbański saw him as a theoretician of social networks – that is, systems of mutual assistance and activities that bring together members of communities that represent an alternative to the rules of the hierarchical, centralized power of state and business. “Working in a network means that a number of independent, equal and usually small groups come together to share knowledge, practice solidarity and act together simultaneously on many levels. The network expresses inner strength. […] Leadership, if needed, is a matter of momentary agreement, and it changes.”8 Therefore, rather than specific architectural solutions, Urbański cast as the main protagonist of his brochure a certain attitude of the architect towards the role of architecture in social life.

Mateusz Gierszon also wrote about anarchism in Poland.9 His selection of projects that are interesting in the context of libertarian ideas also included designs by Kroll and Erskine; he additionally noticed Walter Segal and completed his picture of the participatory threads of Team Ten architecture with an analysis of Giancarlo di Carlo’s projects. Relatively recently, he has also written about projects by John Habraken, Hassan Fathi, John Turner and the Technology Development Group, and he has mentioned Alejandro Aravena’s projects, among others.

A review of Polish anarchist journalism on architecture shows that these authors were particularly interested in eclectic projects. They did not precisely determine the relationship between the discussed projects and the theories and practice of anarchism, nor the criteria for the selection of examples. They did not pay much attention to such determinations, perhaps because they were writing for members of the anarchist movement and they did not need an additional explanation to understand these connections and motivations. The points of reference for the quoted journalists are all those proposals in which the element of participation appears (but the figure of the architect, coordinator and conductor of the design process is also constantly present), and all those experiments in which the design, construction, or use of completed buildings is combined with some form of self-government and associations of users or residents. Self-organization or grassroots democracy – indispensable elements of the anarchist attitude – are neither the only condition nor even the necessary condition for something to be classified as anarchitecture. After all, this trend includes buildings erected in more traditional frames. Anarchitecture does not always strive to create architecture: it is fulfilled both in recovering and reusing spaces and in building specific social relations or democratic co-decision procedures without erecting any buildings or structures (such is the case of cohousing or squatting movements).

It seems that the texts quoted above, especially those by Górski and Urbański, were greatly influenced by the publications of Charles Jencks, some of whose works were published in Poland in the 1980s. Even at the beginning of the twenty-first century, Polish readers had very limited access to foreign publications on architecture, and it so happened that highly polemical texts containing traces of interest in democratic attitudes in design were translated.10 Jencks recognises the importance of anarchist traditions in the beginnings of avant-garde modernism: in the organization of teaching at the Bauhaus and in the concepts of Bruno Taut and Alvar Aalto. He started his discussion of the art of post-revolutionary Russia with a chapter devoted to the “activist tradition” in twentieth-century architecture: he referred to the movements of illegal squatter settlements, including the Peruvian barriads – settlements built spontaneously by residents and then quickly destroyed by the police. “When each one builds and destroys his own home according to his needs and wishes, and when the organization of services must be the result of popular initiative, the kind of brotherly affection foretold in mutualism doctrine develops”11, he noted. In Jencks’ writings of the late 1960s, references to anarchism seem something more than a history lesson. He seems to favour the model of architecture based on grassroots movements and self-organisation, as opposed to modernist social engineering that works for the advantage of the neoliberal order.

In the book’s postscript, titled Architecture and Revolution (the title was a polemic with Le Corbusier and his appeal: “Architecture or revolution”), Jencks directly expressed his views. He mentions rare moments in the history of civilization when “forms of public life were conducive to free and open discussion of issues concerning the whole community”. The benefits which stemmed from this included not only the obvious advantages of self-government – controlling decisions that affected everyone – but also extended to the realm of joys that now sound strange to our ears: “public happiness, the delight of public speaking to reveal one’s identity, the joy of deliberating, sharing one’s views with others and even with the opposition.”12 Referring directly to May 1968, Jencks enthusiastically recalls grassroots decision-making structures in the form of action committees. He saw in them the fruit of all popular revolutions (from the Paris Commune to the October Revolution). The last paragraph of the book is a manifesto of a return to architecture based on social trust: “If today […] we are to have trustworthy architecture, it must find support in a popular revolution which results in a credible form of public life – the council system”.13 It does not seem likely that the council system in this surprising appeal for a new democratic ethics of architecture would refer to anarchist solutions, but it would certainly applaud the disintegration of the existing system of power, not only of ossified models of government, but above all of the neoliberal order.

It is not a coincidence – or perhaps it might be, but nevertheless it is significant – that the criticism of modernism and the appeal for a return to democratic design appeared in Polish journalism under the influence of texts written by the leading critic of postmodernism. In retrospect, there is a feeling that the aesthetics of postmodernism in Poland accompanies the rather ultra-liberal transformations of the period of political transition. If anarchy affects the aesthetics of postmodernism in any way, it is only in the popular understanding, namely as the dominance of uncoordinated, unplanned, and extremely individualistic solutions, subordinated to imprecisely defined and poorly controlled market mechanisms. However, the awareness of anarchitecture in Poland accompanied precisely the postmodern questioning of the authoritarian modernist model. This was also noticed by Gierszon:

In its explorations, the detailed, diverse and individualistic architecture associated with anarchism seems to be consistent with the mainstream postmodern reaction to the hegemony of modernism. However, postmodern architecture that professed to use an archetype – a form that is rooted in culture and comprehensible to all – in fact had shallow and speculative ways of bringing architecture back to broader social groups. […] Although the libertarian critique of the combination of politics and architecture/urban planning was born parallel to postmodernism, in fact it came from completely different stances. First of all, the issue of the architectural form was of secondary importance because it was supposed to be the result of social relations – and it was those relations, manifested in the design and construction process, that were the most important.14

Postmodernism is a style of conservatism; it is the aesthetics of the free market and of elitist individualism; however, in the Polish debate on architecture – the debate on libertarian architecture and the rejection of modernist models – both trends ran in parallel. In my opinion, this is why activists have taken strong anti-modernist positions.

In the recent extensive publication (over sixty examples of the relationship between architecture and anarchism) Architecture and Anarchism: Building without Authority, British researcher Paul Dobraszczyk15 presented an in-depth analysis of anarchitecture as a broad social trend that is not necessarily limited to the activities of anarchist groups. He defined anarchism rather broadly. He took into account its doctrinal diversity and pointed out that we are dealing with a common anarchist attitude rather than a theory that can be clearly catalogued.

All forms of anarchism are founded on self-organization or government from below. Often stemming from a place of radical scepticism of unaccountable authorities, anarchism favours bottom-up self-organization over hierarchy. It is not about disorder but about a different order that is based on the principles of autonomy, voluntary association, self-organisation, mutual aid and direct democracy.16

Dobraszczyk’s text and the selection of the presented examples seem to be guided by the thought of the anarchist writer Colin Ward. After all,

He always argued the values behind anarchism in action are rooted in the things we all do. […] As part of his work, he often embraced everyday subjects such as community allotments, children’s playgrounds, holiday camps, and housing cooperatives. He had a strong and optimistic view in anarchism as an always-present but often latent force in social life that simply needed nurturing to grow.17

A broad understanding of anarchist practices allows Dobraszczyk to present a broad range of examples of anarchist architecture. He groups them around several leading themes: freedom, escape, necessity, protest, ecology, art, speculation, and participation. He discusses examples as diverse as the libertarian Christiania in Copenhagen, Auroville in India, the hippie Slab City in California, the ephemeral, democratically organized communities of big festivals like Burning Man or Rainbow Gatherings or, surprisingly enough, the religious Kumbh Mela festival. On the occasion of the escape theme, he mentions the free, grassroots aesthetics of British plotlands, the Nokken housing estate near Copenhagen, playgrounds designed by Carl Theodor Sørensen in the 1930s in Emdrup near Copenhagen, and camps associated with protests against neoliberal investment mechanisms, including the French ZAD (zone à défendre, zone to defend). He describes ecological buildings (the Street Farm activities in London in the 1970s, examples of urban gardening such as Prinzessinnengärten in Berlin) as well as the “architecture” of mass protests (such as the temporary protest camps at Tahir Square in Cairo in 2011, the Zuccotti during Occupy Wall Street in New York in 2011, and Extinction Rebellion in 2018, i.e., a series of protest actions in London in places dominated by car traffic).

The examples cited in the chapter on necessity are of an entirely different nature. Self-governance enforced by a community that is forced to remain on the margins of dominant economic and social relations should be treated differently than similar actions carried out by choice. Nevertheless, these examples also can be classified as anarchitecture because democratic solutions in terms of land management and examples of social solidarity are evidence of spontaneous cooperation between people in a situation of crisis and the absence of a superior authority. Among other examples, the author discusses “The Jungle” – an illegal camp of immigrants near Calais, brutally liquidated in 2016 by the police.

“Speculations” and “participation” both produce architecture that is close to the traditional sense of the word as they assume the necessity of the designer’s participation and the creation of a unique “work”. This set includes relatively obvious projects like Constant’s New Babylon from 1958–1974, but also, somewhat less obviously, the digital space: from Minecraft to open source projects. Dobraszczyk supplemented the list of “classic” examples of participation known to us from texts by Polish journalists – projects by Giancarlo de Carlo, Lucien Kroll, Ralph Erskine, Walter Segal – with more recent ones, such as Granby Four Streets in Liverpool by the Assemble group from 2013, and Agrocité by the Paris atelier d’architecture autogerée, founded in 2016.

The publication ends with photos showing police officers taking down the ephemeral Antepavillon in 2021, an artistic installation associated with Extinction Rebellion activists that was built in London during the pandemic. The powerful picture at the end reveals, for the first time, the other side of the coin of anarchic actions – the oppressive forces that govern the liberal order of modern cities.

Certainly, not all examples chosen by Dobraszczyk concern doctrinally understood anarchism, and many may not refer to architecture as such (at least when understood as the implementation of a planned building), but they create a suggestive selection of activities related to democratically managed and organized space. Behind most of them are actions that are critical of the liberal vision of the city and that seek to revive broken ties with nature; they even provide examples of environmental activism.

Planned spatial order or self-organization

Self-organization, self-construction, and spontaneous architecture are not an experimental margin of modern construction but a real and perhaps also dominant phenomenon in the organization of the human living environment. Architecture without an architect and cities without planners are the reality of the majority of the human population, either by choice or by necessity. According to Dobraszczyk, the spatial order of some of the cities of the Global North reveals its face to be exclusive and expensive – not only in the material sense. Planning practices related to the development of modern cities has gradually led to the blocking of both democratic mechanisms and citizens’ processes of self-organization. Planning, improving the quality of life, efficiency and hygiene has resulted in increasing centralization of power and professionalization of decisions, thus limiting the individual autonomy of residents. Planning in modern cities constantly and persistently aims to achieve relocation of poverty, spatial segregation, the inevitable processes of gentrification and exclusion at various levels, and ultimately also to the commercial valorisation of urban areas, which follows these phenomena. And yet, not all dimensions of urban life can be controlled and planned. Jane Jacobs notes that cities function well because of neighbourly relations and human exchange.18

The central planning or self-management dilemma is not an easy one to solve, especially from the perspective of a country whose space is the result of abandoning planning altogether. It is enough to mention the discussion about the need for spatial planning, which was so heated and urgent in Poland in the first years of the political transition after 1989. This period was perceived as an era of “anarchic” activities that led to spatial chaos and widespread ugliness. To this day, we remember with nostalgia the modernist city from the times of the People’s Republic of Poland: even though it grew out of an authoritarian political project, it was planned rationally and with care for the quality of space. In the 2011 edition of the Warsaw Under Construction festival (held under the slogan “Back to the city”), the architecture in the times of the political transition was called “parachute architecture”. According to the authors of this term, it did not respect the context: it was forced upon the place, it was aggressive and arbitrary (adhocism comes to mind – a term Jencks applied to selected postmodernist projects). On the occasion of this festival, a conference devoted to this type of built environment was held. Conference participants seemed to equate ostentatious examples of uncontrolled business activity with arbitrary development of abandoned blocks of flats in the former Soviet Union or other “anarchist” activities. In the eyes of the speakers, these were manifestations of the same phenomenon: ugly, flashy buildings, erected without a plan or plainly against the law; superstructures, stalls, glaring signs and advertisements, suggestively called by Piotr Starzyński the “scream of space”, resulted in an urgent need to control that illegal construction, to squeeze it into the framework of superior plans. The publication accompanying the festival is actually a collection of manifestos, including the “manifesto of non-participation”, and it bluntly expresses disagreement with chaotic, unplanned construction. Strong, stern demands were written in capital letters:

HOWEVER, WE DO NOT ALWAYS WANT TO AND ARE NOT ALWAYS ABLE TO PARTICIPATE. WE ALSO HAVE THE RIGHT TO NOT PARTICIPATE. […] AUTHORITIES SHOULD RESPOND VIGILANTLY TO CHANGES, STUDY THE POTENTIAL OF CITIES – AND ESPECIALLY WATCH ALL THAT IS SPONTANEOUS, GRASSROOTS, SELF-GENERATED. THE DISCUSSION ON THE FORMS OF PARTICIPATION CANNOT TAKE PLACE WITHOUT A DEBATE ON THE SOCIAL ORDER.19

Despite the rather democratic character of these appeals, the organizers and commentators were guided by their belief in the strength of the municipal authorities, in the professional approach, and in the need for spatial planning. The key words of the text – coordinated actions, coherence, consistency, professionalism, management, competence – all refer to the exclusive, technocratic model of city management, based on the competence of professionals. Participation with a (justified) right to non-participation (it is no coincidence that the booklet closes with an interview with Markus Miessen about the “nightmare of participation”) can and even must be an important element of urban policy, but only within the framework set for it. It is always an element, but not a subject, not an agent. Anarchy is accused of generating chaos – of unambiguously connecting with the neoliberal individualistic disorder and cluttering the space. Although these accusations raise objections from people who observe the workings of activists – incidentally, they also raise my objections (since 1989, few organizations have spoken more clearly against the neoliberal system than the anarchist community) – they seem to effectively define the unspoken line of the conflict of attitudes discussed in this text, on both sides of the barricade, which are seemingly the same, i.e., anti-liberal. That barricade runs between autonomous self-management and technocratic top-down management. In a city subject to the dictates of planning, self-organization will be present only in designated places, and only if clear rules of participation are observed. It will often be reduced to a convenient simulacrum that legitimizes the liberal order.

However, since we all want to live in pretty, professionally managed cities (and perhaps Polish cities fit this description better today than they did in the 1990s or in the first decade of the twenty-first century) – also, since we are not experts in local planning or construction technologies, and we cannot discuss them; at the same time we do not have time to deal with them, and we are allowed to refrain from participating – why should we even think about the anarchic model of shaping the environment of human life?

According to Dobraszczyk, anarchic architecture is an important alternative for thinking about the future of cities that are now mired in a multi-level crisis. It offers hope for a more inclusive society and ecological construction that are adapted to the needs of a world struggling with scarcity of resources, excess consumption, and authoritarian management models. Anarchitecture enforces the reuse of materials, the economical expenditure of resources, responding to crisis situations, creating support networks, and gaining self-sufficiency. It resembles the societies of the Global North in terms of the ability to self-organize, to make independent decisions or negotiate them in critical situations, and to count on oneself when the convenient paths of political services and consumer services fail. There is tremendous potential in self-organization – a significant feature in the recent difficult times of pandemics, environmental crisis, and war. Anarchitecture also offers an emancipatory chance to the architect’s occupation: it moves the architect from the stance of a social engineer to the role of a mediator and participant in social processes, thus restoring the somewhat strained social trust in this profession. I do not know whether this kind of design and decision process could fully replace structures based on planning, or whether it makes any sense to replace one system with another. Organizing self-organization destroys its essence; self-management cannot be managed or governed. Nevertheless, there is a direction worth taking: not to supervise and not to punish; not to create cities based on separation, parcelling, ordering, clearing and relocation – cities where people have no chance or desire to meet. Anarchitecture does not require nurturing or appreciation or even funding; all it needs is a city that does not subject it to oppressive control and restriction. This can be done without anarchism, and it can be done without architecture. It flourishes at revolutionary meeting points between different people, in the light of mutual visibility, in different situations that we can neither foresee nor plan today.