Kinga Zemła talks to Slava Balbek, a Ukrainian architect

Balbek Bureau, a design studio in Kyiv, was founded fourteen years ago by Ukrainian architects Slava Balbek and Boris Dorogov. The team has created residential, commercial and office architecture; they have also designed interiors, furniture, and decorative elements. They have frequently received awards for their work. Their activities were interrupted on February 24, 2022 by brutal Russian aggression, which forced these designers to regroup and to adapt their architectural knowledge and experience to new conditions and new challenges. To begin with, their RE:Ukraine System initiative responded to the growing demand for temporary settlements that would house internally displaced persons; in the months that followed, they also addressed the issues of rebuilding destroyed villages and towns and protecting cultural assets. As part of this initiative, a platform was created to discuss the role of spatial solutions in the processes of dealing with trauma and commemoration.

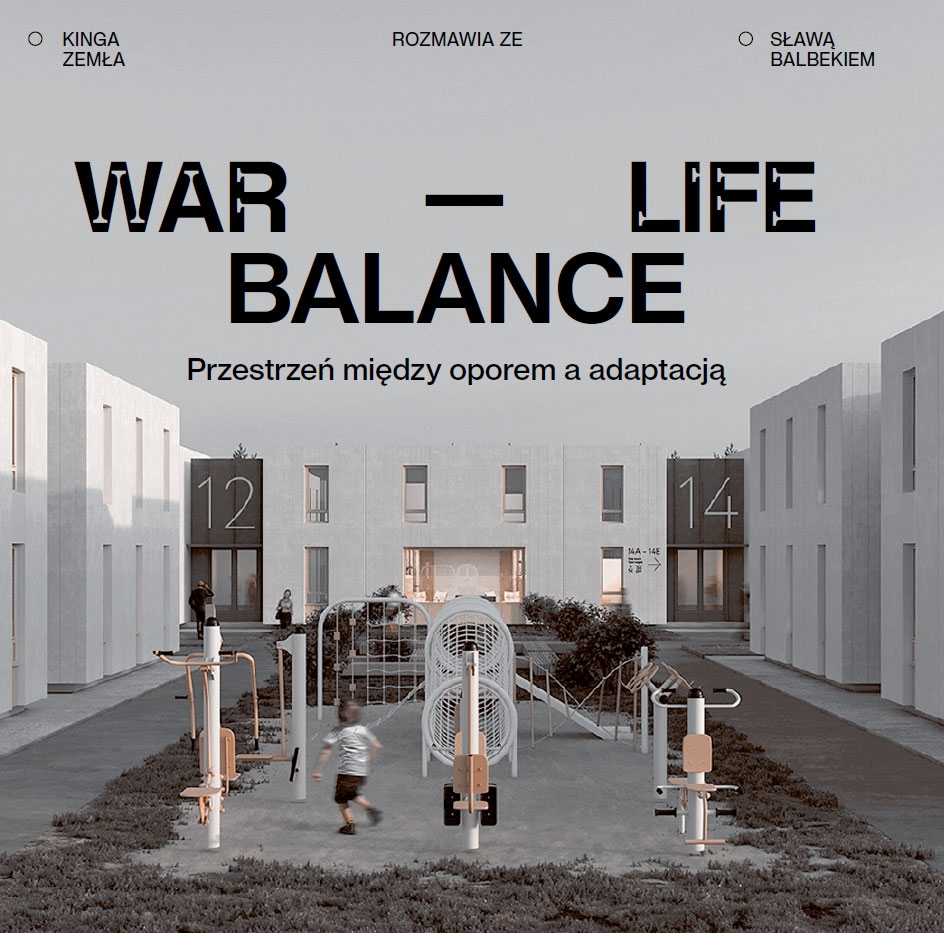

Kinga Zemła: In December last year, you came to Stockholm to talk about the architectural initiative called RE:Ukraine System. That is when we met. During the lecture you gave on December 1, 2022 at the Royal Swedish Academy of Arts, you talked about specific projects and solutions; at the same time, you were forced to constantly expand the context of the story: not so much to explain the spatial conditions for the creation of these projects, but primarily to include the emotions accompanying the alternating processes of resistance and adaptation. Using the rather spooky term war-life balance, you introduced the listeners to the changes that had taken place at Balbek Bureau and in your personal life: you are still active in the field of architecture, but you have also joined the Ukrainian army as a volunteer. It seems to me that there is no way to start this conversation other than by asking about the beginning, that is, about February 24, 2022 and the days that followed.

Slava Balbek: The first days were the hardest. Ensuring your own safety and the safety of your near and dear ones had become an absolute priority. I also consider Balbek Bureau employees to be my near and dear ones. The management team sent out messages, telling them not to worry about costs or salaries and to do everything possible to protect themselves and their families. We tried to reach everyone and help as much as we could. Some decided to leave Kyiv and went to the west of the country, to Lviv; some went abroad, mostly to Poland. Others enlisted in the army and are still fighting on the frontline to this day. Unfortunately, several women, our architect colleagues, were stuck in a village that was being occupied by the aggressor on the outskirts of the capital. In short text messages, they wrote that they had lost their internet connection and were afraid to leave their homes because the streets were full of Russians. Today I am relieved to say that no one on our team was seriously hurt, but at the time we were terrified. Those of us who stayed in Kyiv became involved in providing emergency assistance on the spot. Before the war, the office had a business connection with a chain of cafés, so we decided to organize a food supply chain. For two weeks, we prepared meals and delivered them to shelters and military bases. Around mid-March, we started wondering how to incorporate our architectural knowledge and experience into activities for Ukraine.

At the same time, we understood that if the office was to survive, we had to continue working on the few projects that were not cut short by the war – foreign ones, obviously. We responded to sympathetic e-mails from customers with a slightly forced, light-hearted tone: “everything is fine, no problem, business as usual”. But first, we needed to regroup. From the entire team, we gathered about thirty people capable of working. Not everyone was mentally ready for this, but those who decided that they were simply felt the need to do something.

KZ: So acting has become a form of releasing or blocking out emotions? Anger, despair, helplessness?

SB: Absolutely. We published the first version of the RE:Ukraine Housing project in just ten days – can you imagine? We worked like crazy, practically non-stop. Sometimes I remember that period and I still can’t believe it. We really needed that. Over the last few months, I have seen different reactions and strategies in the face of the crisis. I think that people can be divided into three groups on the basis of these reactions. The first group includes those who become completely paralyzed and are unable to take any action. In the second group, I would classify people who only see a way out of the situation by escaping. The rest, the third group, cannot stand inaction: it is what crushes them, what overwhelms them the most. I do not wish to judge anyone; every person is determined by his or her own individual psychological predisposition. Thanks to our work within the RE:Ukraine System, we have been able to cope with this terrible new reality. We spent about one-fifth of our time doing foreign commercial projects, and the rest of the time we were working on the initiative.

KZ: Before we dive into the RE:Ukraine System, I want to hear about your experiences as a frontline volunteer. When did you decide to sign up? Did you have any experience with the army before the war? I am guessing that if you had ever used a drone, it was to take photos of land plots from a bird’s eye view, at most…

SB: (laughter) Not even that. I had been to a shooting range several times. Also, our entire team had completed a first aid course, which is highly valuable knowledge. Volunteers do not need to have military experience. They sign a contract, which is less restrictive than an official military contract and allows for considerable flexibility both in terms of the time they devote and the duties they perform. You can help in many ways, starting from the distribution of equipment, food, and medicine, or evacuating the injured. Other less obvious forms of support are also offered. For instance, many physiotherapists go to the front to give massages to soldiers. I know a guy who does tattoos there.

I signed up for a special course in drone piloting and war tactics. Only after completing it, in July, did I gain the right to take part in military missions. It didn’t last long, because two months later the rules changed and I would need to get an additional certificate to continue. Because I was trying to strike a balance between RE:Ukraine System and emergency assistance in the occupied territories, I did not give up volunteering, but I mainly acted as a driver. Being in a war zone, close to the front lines, became part of my life. I try to go once a month, for about a week each time. I hope this doesn’t sound weird, but I’ve found that I am no longer able to stay put in Kyiv for long. It is as if I need that adrenaline shot, need to expose myself to risk, otherwise I would fall into stagnation and lose my focus. Now I know this about myself.

KZ: On the one hand, you are regularly involved in the war zone; on the other hand, you are developing RE:Ukraine System. Is it fair to say that this initiative grew out of the need not only to act and cope with the situation, but also to resist?

SB: It grew directly out of our experiences. We had to abandon our apartments, move from place to place, hide in shelters. To varying degrees, we also became refugees. At the same time, all these transitions had a spatial dimension and were an obvious architectural theme. RE:Ukraine System brings together several different projects, each of which has a specific position in the hierarchy of needs. Despite the structure being clear from today’s point of view, the initiative has developed gradually, consisting of organic reactions to the subsequent stages of the war. Like a mirror, it reflects the evolution of our experiences, emotions, and thoughts.

I have mentioned the indisputable priority of physical security. For people whose homes have been destroyed or who have had to flee from the occupied territories, it is of utmost importance to find a temporary place to stay. That is why RE:Ukraine System started with a project of settlements for internally displaced persons; we called it RE:Ukraine Housing. Only when this basic need is met can we move beyond the individual perspective towards a community, for example a neighbourhood community. In the face of a shared fate, mutual support arises immediately and often manifests itself in completely prosaic, mundane activities, such as repairing damaged fences. It is to the community, composed of individual citizens, neighbours, and local authorities, that we dedicated RE:Ukraine Villages. It is a catalogue of country houses and an online tool: a set of architectural and construction tips and directions, useful whenever reconstruction is necessary. Collaboration to restore a state of quasi-normality to private space gives rise to concern for the more broadly understood surroundings, for example, infrastructure, cultural and educational centres, symbolic places and objects. In this spirit, the RE:Ukraine Monuments was created: a monument protection system. The RE:Ukraine Memories and RE:Ukraine Visions projects tackle space – they transform it into a tool for building collective memory and processing trauma. I wish to emphasize once again that although the various branches of RE:Ukraine System now form a narrative whole, in March last year we were working in a mode of pure chaos. We diagnosed the first fundamental need – providing decent conditions for temporary accommodation – and started dealing with that.

KZ: All your projects operate within the spectrum of temporariness. In Stockholm, you emphasized that they belong to this dimension of life. You have decided not to deal with either long-term solutions or – at the other end of the spectrum – with emergency solutions.

SB: There are simple reasons behind this decision. The government is already operating in emergency mode. It focuses primarily on rebuilding critical infrastructure and organizing makeshift settlements made of containers. Moreover, in a situation of sudden crisis – for example, the need to swiftly escape – emergency solutions suggest themselves due to the lack of alternatives. You go to live with friends or relatives or in a hastily constructed camp. While these places work well as immediate remedies, in most cases they are not suitable for long-term stays. The problem is that this unstable situation could persist for years, and with it, life in precarious conditions can also persist. People condemned to living in a container home or on a sofa in someone’s living room are waiting to return to “normal”; they are waiting to rebuild their house or village. This perspective remains distant and is based on a long-term vision that assumes a successful conclusion to the war. RE:Ukraine Housing is a response to this temporary circumstance; it is intended to provide decent living conditions in the period in between. We propose a strategy that is both parallel and complementary to emergency solutions and long-term projects. We are happy that government representatives noticed this, and we were invited to several meetings at the ministries of culture and infrastructure. We hope to establish partnership-based collaboration with the authorities. Regardless of whether this happens or not, all projects within the RE:Ukraine System are available, free of charge, to anyone who would like to make use of them, whether it is at the level of private entities, local communities, or public authorities.

KZ: You put emphasis on the fact that most refugees do not wish to be resettled far away from the places where they used to live before the war. You also point out that temporary settlements should be established close to cities, preferably connected to their urban systems. How does one implement these demands in practice? How is the process of acquiring plots going, and what does the cooperation with local governments look like? The pilot project is being put into operation in the Vorzel urban estate in the Bucha region.

SB: In January, after completing all the formalities, construction finally began. The development is being built on plots belonging to the local municipality, with money raised from a collection. According to the agreement we concluded with the authorities in Bucha, for one year from the date of settlement this place will be supervised by a group of architects from our office. They will be delegated there to conduct analyses and deepen our knowledge of the residents’ needs. Later on, management will be taken over by the local government. Unfortunately, because the area belongs to the municipality, the preparation and approval of the required documentation took almost five months! RE:Ukraine Housing is a modular system, so according to the plan, construction should have been completed within three months. Of course, in war conditions it is difficult to make any predictions. Shelling or power outages might render the task more difficult, and it will likely take longer to complete. This makes the overly extensive bureaucratic procedure all the more absurd. However, we decided to go through all its stages carefully and fastidiously in order to collect constructive comments and suggestions for improvements and then pass them on to government representatives. To strengthen our argument, we will also refer to the experience of the second pilot project in Lutsk. We are implementing it on the initiative of a group of private investors, under their supervision and at their expense. That camp is being built very fast.

KZ: You expressed the goal of the transitional architecture of the RE:Ukraine Housing modular system with a concise slogan: from standard minimum to minimum comfort. What do you consider to be the minimal comfort in a refugee settlement, especially considering that a temporary condition tends to slide into the state of undesirable permanence?

SB: First of all, we care about introducing some normality to the refugee experience through a space that ensures privacy and freedom at the same time. Both of these dimensions of living are missing in a container home or on a couch in someone else’s living room. At the level of the urban plan and in individual buildings alike, we have made provisions for common spaces where residents can nurture bonds and relationships with each other or entertain guests. Moreover, our understanding of minimum comfort comes down to basic dimensions, for example the width of the corridor: it should afford comfortable passage in a wheelchair and not cause claustrophobia. Sometimes a dozen or several dozen additional centimetres are enough to raise the standard if they significantly influence the perception of the space by its users. We need to remember that we are shaping a living environment for people in dire circumstances, burdened with the trauma of war. We would like this environment to act as a neutral setting for mental recovery, not a source of further suffering or anxiety. Camp residents need to regain strength to cope with the reality of war. They will not regain their strength in a space that is yet another burden for them.

KZ: During the lecture, you emphasized the connection between aesthetics and decent living conditions. Of course, today you do not design expensive, sophisticated interiors or façades, but you still include aesthetics in your ideological programs, although they are not a practical dimension of shelter architecture. I assume that aesthetics’ role and impact on the user’s mental condition depends on individual adaptation and habits. Some will be sensitive to its absence; others will hardly notice.

SB: You perceived that we propose the aesthetics of cheap and simple solutions. Nevertheless, we treat those seriously – as carriers of normality in an abnormal situation. We wish to create a space conducive to the regeneration of people who carry within them images of destruction and obliteration. What is more, although we design places for temporary living, we do not consider these settlements to be temporary architecture that is intended for demolition on the day the war ends. Houses built in a modular system, with a wooden structure, are durable and can last for many years. We imagine that after the war these housing estates will be transformed into offices or educational complexes. Being mindful of the building’s life cycle, we do not want to give up the aesthetic layer.

KZ: When you put it this way, I also think about the more personal dimension of practicing the profession of architect. It seems that, regardless of the circumstances, you wish to work in a way that is as close as possible to the one you knew before the war, without giving up the values that always guided you. Russian aggression has already forced you to design refugee camps instead of ordinary settlements. I sense a form of resistance on an individual level.

SB: I fully agree with this interpretation. In an architect’s work, the search for beauty is associated with artistic expression, even if we do not typically devote a significant portion of time and work on every project to beauty. During a war, a painter will still create paintings and a poet will still write poems, although the creative process is interrupted by the sounds of sirens and the necessity to evacuate before the next air raid. We are going through different stages of this war. We transform our experiences and emotions into new projects that are created in response to the changing reality. In hindsight, we will probably see and recognize subsequent stages in our works: the occupation of Kherson, of Kharkiv Oblast, the tragedy in Dnipro, and so forth. I sincerely hope that you never come to experience anything like this.

KZ: It is hard for me to imagine working in an office in such conditions.

SB: Indeed, it is not easy, but we have developed operating patterns. People are surprisingly adaptable; they adjust really quickly even to the worst conditions imaginable. Last November, I noticed that some people on the team – as well as some of the volunteers who were helping us – were falling into a stagnation of prolonged fatigue and devastation. I suggested that we prepare projects for several foreign competitions in order to break away from what was happening around us and give ourselves some time to do something enjoyable, something that would make us happy. The deadline for submitting proposals was at the end of the month, and that is when regular power outages began. We did not want to give up; in a way, the inaction caused by the blackouts depressed us even more; it deepened the feeling of helplessness. We drew a lot of sketches by hand, but we needed computers. We had to set up a minivan with a power generator; we parked it near the office. We started the engine, turned on the generator, and plugged an extension cord through the window. Some people worked in their cars. All my friends already have their own power generators; they have learned how to jump-start them, to change the oil, to switch to diesel. Before, they had not the faintest idea how to use these things.

In order not to go crazy, we endeavoured to approach everyday life with humour, in a relaxed way, like a twisted game. Of course, we knew that the alarms heralded real danger. Those motherfuckers were trying to hit critical infrastructure, and suddenly seventy missiles were falling on Kyiv. Usually in such situations the electricity was turned off first. The alarms were howling, you would be waiting for an explosion, missiles were striking; the noise was terrifying. And then, well… we would go to the minivan and try to keep working.

KZ: (silence) Since we are talking about the shelling, let us talk about RE:Ukraine Monuments. You designed a simple protective structure for monuments, more solid and aesthetic than traditional mountains of sandbags. As an aesthetic solution, this project seems to be part of the process of adapting space to the new normal. The story of its pilot implementation disarms me. After installation, the structure survived for several months before it was significantly damaged during the shelling of the city. The monument was not damaged, which proves the structure’s efficacy. You immediately raised the steel frame again and attached the panels. What admirable tenacity. Doesn’t helplessness creep in, though, when you see the fruits of your labour literally blown up?

SB: What drives me is not so much tenacity but faith in statistics (laughter). The probability of another explosion in the same location is low, especially if there are no objects of military importance in the area. The monument is located near a park and a kindergarten. You mentioned the new normal. Restoring normality – to any extent – is crucial for mental health, and the “normal” includes places that are an integral part of everyday life. A few hours after the explosion, residents are always seen cleaning the streets, repairing windows, and pouring asphalt. Living in an atmosphere of destruction is extremely emotionally taxing.

Functioning in the condition of temporariness has transformed the perspective of perceiving the effects of one’s own work, and this applies not only to RE: Ukraine Monuments. The lens through which we assessed our performance before the war shifted to a focus on achieving goals in small steps. We consider each of our undertakings valuable if it benefits at least one person, even for a short time: if it arouses hope, gives strength or comfort to someone. Supporting Ukrainian society is our form of resistance. It is the soldiers who fight at the front – but we are also operating in defensive and striking mode. In the wartime mode, we do not expect architecture to last, so we cannot give up just because what we built has turned to dust.

KZ: In RE:Ukraine Memories you adopted the opposite tactics: instead of repairing and restoring normality, you preserved – in destroyed form – a bridge blown up by the Ukrainian army at the beginning of the war. The famous bridge in Irpin became a symbol of not just resistance but also of the tragedy of thousands of people evacuated from under its collapsed body during Russian shelling. The concept is to perpetuate the memory of these events in an extremely meaningful way. You reached for the memory of an open wound.

SB: For me, this is the most difficult, most painful of all projects. Our proposal sparked a heated discussion. Some recipients welcomed it, but people from Irpin hated it. They do not want to keep the destroyed bridge or see it in this condition because they live in destroyed houses, in destroyed villages, in a destroyed region. We understand their pain perfectly, but we are trying to look beyond its horizon to the times when everything will have been recovered and rebuilt. Today, every place is marked by the stigma of war – the damaged buildings, villages, and cities are a constant reminder of it and bring the war to the fore. In a few years or a decade or so, these traces will disappear. Perhaps it would be a clear testimony – not only of suffering, but also of the courage and dignity with which we faced this aggression – to preserve the bridge in its present condition, an indelible mark on the landscape. We also see it as a way to stimulate the debate, which we believe should start now rather than later. In the future, we will lose some of our experiences and reflections, and the range of concepts for describing them will narrow significantly. By postponing this conversation until peacetime, we risk false notes creeping into it. We need to start working through all this right away. Together.

KZ: Self-organization and grassroots community-binding action seem to be at the basis of your ideas about the reconstruction of Ukraine. You mentioned that the government currently has other problems than focusing on the comprehensive reconstruction of destroyed villages but that the reconstruction is happening nevertheless – carried out by inhabitants with the help of volunteers and architects. In the RE:Ukraine Villages virtual catalogue, you propose original typologies from various regions of Ukraine, a traditional colour palette, vernacular details and materials. On the one hand, you care about maintaining architectural heritage, but you entrust this task to local communities. Anyone can download a PDF from your catalogue with a ready-made, dimensioned project and instructions for its implementation. Do you consider self-reconstruction to be a pillar of the country’s spatial renewal after the end of the war?

SB: Yes, but I have to make one correction. We are not waiting for the unspecified, long-awaited day of the end of the war to begin large-scale reconstruction. It is just happening already. Step by step, region by region, with or without our participation, in all liberated areas, people are gathering up their strength, mobilizing, and trying to rebuild their houses, villages, and towns. Nobody wants to be displaced; everyone prefers to stay in their hometown or region, with their family, friends and neighbours, even in towns less than thirty kilometres away from the front line. At the beginning of January this year, I was in the area of Kharkiv, which was completely destroyed. Humanitarian aid had already arrived: food, warm clothes and power generators had been delivered. I talked to the women, inhabitants of the local villages, and they kept repeating: “Slava, we have been provided with all the basic products to survive the winter. Now we need construction materials so that we can rebuild our houses and villages!” It makes no sense to wait. RE:Ukraine Villages is suitable for both individual use and local government activities. We have developed this catalogue not because we believe in human agency; we just keep witnessing it, all the time. There is incredible potential and energy in the strength of the community.

KZ: One of your newest ideas is RE:Ukraine Visions. You propose developing a virtual tool that, based on an image of destruction – a destroyed house, street, or square – would generate a simple visualization of the future, after reconstruction. You call this the architecture of solace. For me, it brings to mind Jonathan Lear’s “radical hope”, but not so much because of the hope it offers (it has little in common with the term coined by the philosopher), but because of its emphasis on the role of the imaginative process in overcoming life’s difficulties. Lear stresses that in radical circumstances, when known and familiar concepts are not sufficient to describe the situation, new ones must be created to face that. If we use our imagination, it becomes easier. Imaginary pictures or visions can be transformed into new meanings. Individuals often replace the community in doing so: poets, priests, or leaders. Compared to other RE:Ukraine projects, this system seems the least practical, but you decided to include it in the mainstream solutions needed in the temporary situation. What experiences led to its creation?

SB: In order to be able to do something, you first have to imagine it. You are an architect, so you understand this mechanism perfectly. During your studies and later professional practice, you exercised your spatial imagination. The tools that you developed during this time are useful not only for visualizing space. You know that the better you visualize your goal, the easier it will be for you to plan your way towards it. Not everyone can do this. Some people look at destruction and they see only destruction: they cannot go beyond it, free themselves from it, or believe that something can happen after it. Simple graphics generated by RE:Ukraine Visions are intended to help you visualize your dream and thus awaken the desire to make it come true. It will also work as a practical carrier of ideas. For example, someone wants to build a new school on the ruins of the old one. RE:Ukraine Visions will generate five different visualizations. You can show these to other people, try to convince them to accept the idea; you can discuss the details, raise funds for reconstruction… We will offer light at the end of the tunnel, powered by artificial intelligence; the work is still in progress. Similarly to RE:Ukraine Villages, the team of architects began by analysing typologies, architectural styles, uses and functions, and other components. After feeding the algorithm with this knowledge, the mechanism will read the location and photos from before the war and add layers to the image of the destroyed surroundings. The user will upload a photo and complete twelve steps in the application, which will then present several scenarios of what this place could look like in the future.

KZ: How does your team imagine the future, hopefully post-war and victorious, although probably full of challenges?

SB: In the long term, it will be important to create and refine local master plans and change the construction laws. We are hoping to take part in this. Although RE:Ukraine System emerged from the reality of war, it will remain with us for many years to come, after the victory. We see it as an initiative incorporated into comprehensive social processes rather than as a project that is committed, implemented – and completed, finished. Part of our team will continue to supervise its development. That is the plan, although funding obviously remains a challenge. It is easy to raise ten thousand dollars online for a drone that will most likely crash after a few days, but architectural initiatives are not as popular. However, we believe that we will be able to continue. We are getting support from abroad, also from Poland. I don’t think anyone anywhere supports us as much as Poles do, on various levels. I wish to thank you very much for this, and also for today’s conversation and the opportunity to talk about RE:Ukraine System.

KZ: Poles actually understand that although you are fighting this war alone – albeit with the support of the West, but essentially alone – this is not just your war. We also owe Ukrainians our gratitude. I wish you a lot of strength, Slava, and I hope that we will meet again soon, perhaps in a free Ukraine.