Contemporary Czech architecture

The Velvet Revolution of 1989, along with the transition from the totalitarian to the democratic system, also brought about basic changes in Czech architecture. At the beginning, people would turn to the past rather than to the future. Not only the general public, but also specialists paid tribute to the image of the “First Republic”, that is to the inter-war Czechoslovakia as the last culturally and socially authentic epoch in the history of the country. The renewal of the modernist country in the post-modern world was impossible, but no one was aware of this in the early 1990s. Life under communism, especially in the period of normalisation,1 went on as if in a frozen time; any movement in the society was frozen, and due to the different politico-social reality and the lack of information, it was very difficult to form an opinion about the changes which took place in Western Europe at the time. Even with its best achievements, the architecture of the 1970s and 1980s, maintained in the styles of late modernism and brutalism, was often associated with the political ideology of normalisation, and for this reason it was rejected particularly by the general public. The quality of building construction was a widely discussed subject in the post-revolution period of the 1990s. As a reaction to a low level of performance and material poverty of the socialist construction industry, solidity, resistance and quality of traditional materials were appreciated. The architectonic and construction production of the First Czechoslovak Republic was considered a standard which everyone was supposed to refer to.

In inter-war Czechoslovakia, modernist architecture held a strong position and expressed the aspirations of emancipation among the cultural elite. Apart from the post-war delight and optimism, there was a desire to break off the relationships with Austria, to be released from the Central European context, and enter the Western – French and English – cultural circle. Katerina Ruedi, an American historian of architecture of Czech and Swiss origin, demonstrated that the First Czechoslovak Republic of the 1920s and 1930s used modernist architecture as an expression of national ideology, the purpose of which was to explicitly distinguish between the institutions of the new republic which was geopolitically oriented towards Western Europe and the United States of America and the Austro-Hungarian institutions.2 New offices, schools, hospitals and other buildings of public use were built in the modernist style. Thus, they expressed not only the efficiency of the new country, but most of all the will to depart from the past and the faith in the future. This optimistic ethos turned out to be valid again in the 1990s, when neo-modernist architecture became the desired symbol of the society’s revival. However, as we will see in the following part of this essay, the symbolic functions of this architecture were revealed in a specialist debate taking place among a group of experts, whereas in the sphere of construction of buildings itself they were much less visible.

The revival of social life after 1989 found its expression most of all in the architecture of singular representative buildings, and rarely in the design of the public space or urban planning. Unlike in the well-known case of the First Republic, here neither the country nor the districts, cities, local authorities were investors any more – and even if they were, then it would only concern a one-off order of specific buildings rather than projects of entire architectonic or urban complexes. At the beginning, the most visible investors were private companies who provided buildings to meet their own needs; gradually, more or less from the mid-1990s onwards, they were also followed by development companies. From 1989 the country in symbiosis with “the national party” was ubiquitous, and therefore nobody wanted to see it play the part of a strong actor in social life. According to a universal belief in the power of the “invisible hand” of the market and money as credible measures of quality, in the 1990s the first important investors were banks and insurance companies, which continued to appear with incredible speed throughout the country. In most cases, they would refurbish the already existing buildings: the important aspects were the pace of the realisation of the project and the “formal” appearance, which would far too often manifest itself through decorative elements using materials and colours that were normally unavailable and employing a style of classical origin that was not entirely comprehensible within the context of Czech postmodernism. The exposition of these simulacra of success apparently matched the taste of the majority. To describe the buildings stylised following the prefabricated aesthetics of postmodernism (no matter whether they were office buildings or houses), in the Czech linguistic circle the term of the “enterprising baroque” was soon adopted, referring to the motley of colours and the exuberance of decorative elements on the façade and inside these buildings.

Practically throughout the 1990s in the Czech Republic, building construction developed on a small scale, while the financial turnover on the market and the availability of mature financial products, in particular long-term credit loans, changed very slowly. The scale of investment, and therefore the size of buildings and architectonic complexes, started to increase around the year 2000 due to the growing presence of strong investors. Access to technology and materials also improved. By 2000, the Czech construction industry was essentially meeting all European standards. During the construction of big buildings with strict financial management, complying with norms was more important than the previously cherished skill of improvisation. The anonymous office buildings and massive shopping centres which a few decades earlier had flooded the developed countries of Europe and the USA were created on a mass scale. As Ruedi says, “The built product of modernisation is not modern architecture but Junkspace.”3 The dream of the revival of solid modernism which the Czech architects had in the 1990s dissolved among the ex-urbanisation of the private building development that spread along the highways on the outskirts of Prague, Brno, Ostrava and other cities.

The unique buildings that stand out against the background of those erected in the 1990s are the reserved neo-modernist houses designed mostly by architects from Prague and Brno. Among the most characteristic buildings of the first post-revolutionary decade are the Prague projects executed by Václav Alda, Petr Dvořák, Martin Němec and Ján Stempel, who worked together at the ADNS atelier. They succeeded in reviving the style of the interwar modernism and in creating a distinct trademark distinguished by a reserved formal modernist code. Their office buildings in the centre of Prague still number among the best achievements of the city architecture after 1989: the building of the Czechoslovakian Commercial Bank (ČSOB) on Anglická Street (1996), Vinohrady Office Centre on Římská Street (1995) – they are highly regarded for their neo-functional style authenticated through perfect technical execution. At this point in time, it is difficult to imagine a speculative office building which is completely covered by shiny Brazilian granite inlays, with the window frames made of Scandinavian pine with wooden blinds and in which the materials as well as the interior design are the embodiment of solidity. The peculiar hybrid of the old and the new world is embodied by the corner building of the Generali Insurance Group which is situated in Prague’s Vinohrady neighbourhood (1994) and designed by Martin Kotík. The façade of the building on Bělehradská Street was covered by stone inlays, and through its size corresponds with the adjacent tenement houses of the 1930s, whereas the second elevation – through its aerodynamic shape – reflects the traffic flow in the busy city centre street: it reveals the time of its creation well, an even its impeccable surface announces the near future when the stone neo-modernism as an aesthetic norm will give way to the charm of the super-modern glass façades of the digital era.

An original variety of neo-modernist architecture was created by the group of young architects from the “Obecní Dům” (“Town House”) association in Brno, the Czech Republic’s second largest city, which is famous for its strong modernist tradition of architecture where the “white” modernism meets the more conservative line of modern aesthetics. From the very beginning, the Brno architects have attempted to refer to the tradition of solid building construction in a modern spirit and have continued the line of “conservative modernism” based on the contextual approach to design, reserved proportions, solid materials and a high quality of building construction. Looking back, it becomes clearer that the residential and commercial house on the corner of Josefská and Novobranská Streets (2003) designed by Petr Pelčák and the “Kapitol” house (2000) by Ludvík Grym, Jan Sapák and Jindřich Škrabal have a high urban quality. Their work has also been recognised internationally: in 1997 a prestigious international jury awarded the building of the IPB bank in Brno (1995), the creation of Aleš Burian and Gustav Křivinka, by shortlisting it along with 33 other finalists of the European Union Prize for Contemporary Architecture – the Mies van der Rohe Award.

The new image of Prague and Brno is enhanced mostly by the buildings of private investors. National institutions did not turn out to be suitable for the role of investor in the construction industry: apparently the need for representative presence is not one of the features of the current post-modernist (and post-totalitarian) democracy. As far as publicly funded buildings are concerned, contemporary architecture of good quality is surprisingly doing better in the country than in big cities. Perhaps this is due to the fact that the decision process is usually shorter, while the scope of investment is smaller; but perhaps it is due to the presence of strong visionary personalities who lead the city or the region. Litomyšl, a small town in the eastern part of the Czech Republic, has a unique history and abounds in monuments of architecture which were enhanced with a group of high-quality modern buildings erected at the turn of the 21st century. The first post-revolution town mayor, Miroslav Brýdl, displayed a forward-looking approach when he realised that the society could not be rebuilt without reconstructing the common space and buildings of public use. He therefore initiated a range of projects which were also continued by his successor. The town of 10,000 inhabitants obtained many modern buildings designed mostly by architects from Brno belonging to the circle of the Town House (i.e. a sports hall and a primary school, Aleš Burian and Gustav Křivinka, 1998; a winter stadium, designed by the same architects, 2005; the reconstruction and expansion of the swimming pool, Petr Hrůša and Petr Pelčák, 1995), but also by other leading Czech architects (the transformation of a brewery into a training and culture centre, Josef Pleskot / AP Atelier, 2006; a city swimming pool, Antonín Novák i Petr Valenta / DRNH, 2010), not to mention the transformation of the monastery garden (Zdeněk Sendler, 2000), the square and other public spaces in the historical city centre.

Characteristic is the fact that the modern Litomyšl is renowned most of all for its sport and recreation buildings and less for its national administration buildings. As we have already mentioned, among the new buildings which have been erected in the Czech Republic within the last 20 years and which are worth attention there are hardly any town halls, office buildings or any important cultural institutions, like museums, galleries or concert halls. There are so few interesting architecture pieces funded by public money that there is no point creating further topological categories. Hence, it is surprising and comforting that the prototypical public building in the Czech Republic after 1989 is a library. We can quickly find several examples, like the buildings constructed from scratch in big cities as well as interesting revitalisation projects of older buildings that meet the needs of local libraries. The characteristic feature of the contemporary situation is that these public buildings which – as education centres – dominated municipal spaces are now in various complicated urban situations or they become the revitalisation projects of the former industrial or technical buildings.

The most characteristic projects of recent years are two libraries which were designed by a young group called Projektil architekti (Roman Brychta, Adam Halíř, Petr Lešek and Ondřej Hofmeister) and which draw our attention to their “non-architectonic” form. They take a critical stance neither towards mass taste nor towards neo-modernist architecture by referring to its modernist origin in a free way. Their style is mostly guided by direct circumstances, by the place and the demands of use rather than by any a priori aesthetic ideas. The contrast between the select neo-modernist form of municipal buildings recognised with awards in the 1990s and the contemporary lonely buildings aptly reflects the metamorphosis of the social mood in the Czech Republic: it symbolises the moment of transition from a strong feeling of belonging and responsibility for maintaining the historical continuity to the perspective which is typical of the individualist society that does not turn to the future or create great visions, but tends to react to the current situation in a calm and pragmatic way.

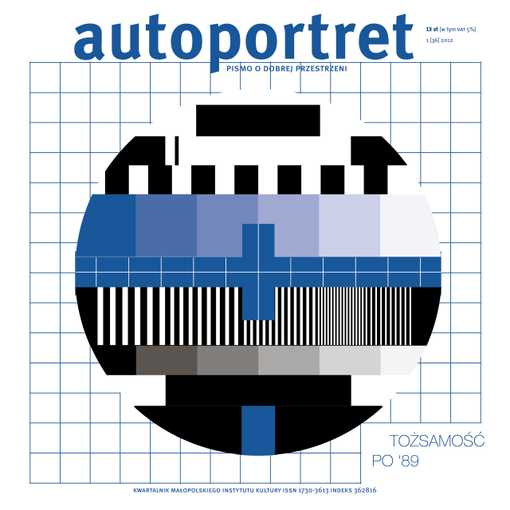

The library building in Hradec Králové (2008), which is situated on the bank of the Orlice river, acquired an individual and easily recognisable form due to its characteristic plan – in the shape of the letter X. This form was not designed for effect, but it has its own urban-creative dimension. It is situated in the exposed but undefined place between the inner and the outer city district. Its definite character works as “urban acupuncture,” in the spirit of Manuel de Solà-Morales:4 as a discreet interference into urban tissues, which carries with itself the potential of initiating changes in a wider environment; it constitutes more a robust urban-creative tool in the chaotic contemporary world rather than a rigid design. The National Technical Library in Prague (2009) is situated on the grounds of a high school of technology, next to the campus and student accommodation. It is a public building of a new kind which is devoid of any hierarchy: the building on a rounded square plan is “the same everywhere,” it has four entrances on four sides, although they are not visible at first sight. You need to come up very close, and only when you stop seeing the whole façade can you find an entrance. The ground floor of the library is a sheltered extension of the university campus; it is a free space where you can find shops, cafés, a lecture hall and a public branch of the city library – in a nutshell, it is a space open to everyone. The heterogenic environment of the contemporary city (or network) corresponds with the interior aesthetics of the building, which is as unclean and fragmentary as the contemporary public space. The half-transparent façade coat made of Gorilla glass panels gives an impression of waves, and blurs the physical borders of the building whose space identity is blurred, but still distinct. Perhaps, this visually poor architecture is the most appropriate expression of our times: the epoch in which identity is constantly undermined through the processes of virtualisation and through being created anew in the network of current relationships.

Translated into English by Agata Masłowska