Marta Karpińska and Michał Wiśniewski talk to Stanisław Deńko – architect, lecturer, winner of the honorary award of the SARP Polish Architects’ Association.

Marta Karpińska: The Embassy in New Delhi, which you co-authored with Professor Witold Cęckiewicz, is one of the most interesting examples of Polish architecture of the 20th century. We would like to talk about this project in the context of the regionalism issue – we are interested in the realization of a modernist design, as created by a team of Polish architects and engineers in collaboration with Indian designers and contractors; we are curious to know how local conditions influenced the final outcome. Let us start from the beginning – from your preparations to enter the competition.

SD: At that time Google search did not exist, and so our main source of information was the literature available in the People’s Republic of Poland (PRL). By a lucky coincidence, before the competition for the design of the embassy in New Delhi, I took part, together with Krzysztof Lenartowicz, in another architectural competition, for a complex of government buildings in Dar es Salaam, the capital of Tanzania. Among the jury of that competition was Yoshinobu Ashihara, Japanese author of the book Exterior Design in Architecture, first published in English in 1970. We managed to get hold of that book, and in fact we continue to use it even today. Ashihara’s book is an analysis of space that is very helpful in the design process – in my opinion, the reading of it enabled us to obtain an honourable mention in that first competition. And it was not an easy feat – as far as I can remember our project was one of the top fifteen, whittled down from a hundred and thirty submissions. Ashihara emphasized the aspects that needed to be considered – the climate, the local context, the cultural conditions. This knowledge was very useful to us, and it was precisely those factors specific to the place that we took into account in our work. We were also greatly influenced by Le Corbusier’s architecture in Chandigarh, as a symbol of thought that revolutionized modernism. Although Le Corbusier’s design was compromised by a faulty execution,it was still a very valuable source of inspiration. On our first trip to India we visited the complex of government buildings, back then already abandoned by its users. I did not know much about Chandigarh until twenty years after we designed the embassy in New Delhi – it turned out that the entire city was flourishing, except for the government buildings, because the ultimate plan to move the government headquarters to the Punjab, to a unit designed by Le Corbusier, had failed. During my stay there, these buildings were occupied by the army – I remember a funny scene in front of the house of the would-be parliament: a soldier, half-stripped, sitting in a chair in front of the building in scorching heat, having his hair cut by a barber.

MK: So at the stage of the competition design, you only knew of Chandigarh from published materials?

SD: Yes, the knowledge of this architecture – of the kind of modernism which takes into account climate-related issues – was only available to us, at that time, by way of publications. And when it comes to designing for hot climates, there are two factors to consider: first, the temperature and the sunlight exposure, and secondly, the ventilation, ways of ventilating the interior. It was precisely these factors that led to our decision to raise the main part of the embassy building above the ground level – thus creating a shaded zone, while also facilitating the ventilation of the area. The plot was very tight, and freeing up the space of the ground floor, we were also able to use it for representative purposes, and we managed to fit in parking spaces, located in shaded areas. This particular design decision was very important, and its correctness was evident only on site, during our first visit to New Delhi, when we also had a chance to visit such historical architectural sites as the 16th-century Fatehpur Sikri. The characteristic feature of this architecture was the open ground floor area, the arcades, the interweaving of spaces.

MK: Was the information on the climate in New Delhi a part of the terms of the competition?

SD: No. The competition guidelines only concerned a functional program, which, incidentally, was very extensive: we had to incorporate the commercial attache’s office, a hotel, a residential area, a school together with a multipurpose conference room, and the ambassador’s residence. It can be said that the embassy building was more of an urban complex than a single building.

MK: And did you manage to get hold of any literature on New Delhi?

SD: Only papers devoted to the accomplishments of Edward Lutyens, author of the New Delhi urban planning concept, implemented as of the beginning of 1912. Nevertheless, we were looking at it through the prism of a critical evaluation of English imperial architecture. We thought that the embassy should aim not so much at showing the strength of our country, but instead, it should strive to represent Polish culture.

Michał Wiśniewski: And how did the investor – that is, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of

the People’s Republic of Poland – define the requirements in regard to the form of the building? Was there an emphasis on conveying specific ideological content?

SD: We had complete freedom in developing the building’s architecture. However, the question remained of how to show our indigenous cultural elements that should be present in such a building. It was difficult to apply our native architecture in this geographical context, in fact, it would be completely unreasonable to try. We were more inclined to show that we were catching up with the civilized world in terms of using the latest technologies available in the 1970s. We wanted the architecture – the slim columns supporting the raised structure – to represent the high level of our technological advancement. The concrete used to build the embassy was really well cast – at that time, we would not have been able to have done it so well within Poland, but there in India, we could, and we did. The very fact of using the raw, “exposed” concrete was a great accomplishment, inspired by what Le Corbusier did in Chandigarh. All those modern elements that we used – the large-area glazing, the double roof – were intended to testify to our awareness of modernity, technological possibilities, and local factors. The specific features of the culture of our own country, on the other hand, could be presented in the interiors, through the design of their décor, of such equipment and furnishings as the coffered ceiling in the residence of the ambassador, inspired by the Wawel (royal castle in Krakow) chambers, or furniture design.

MW: We have seen drawings of the furniture design for the embassy in the archives of the Cracow University of Technology – and we were surprised by the number and variety of the proposed solutions: from wicker furniture, to elements of the Zakopane Style, to leather armchairs and rattan furniture – all of Polish design in a nutshell. Were the interior furniture designs ever implemented?

SD: Yes, they were executed, and the results are still in situ today. It is a whole range of furnishings, a collection. Now that the embassy is to be modernized, we are very worried that the interiors we designed might be destroyed, for instance because in the meantime, the fire regulations have changed. Unfortunately, I have no photos of the embassy interior, and we were not invited to the opening ceremony.

MW: What was the embassy competition like?

SD: There were eight design teams, including three strong teams from Warsaw – the competition was fierce. What was important for the evaluation of our work was the model that we developed to the scale of 1: 500 – in fact, this kind of mock-up was required from all participants. When Professor Cęckiewicz invited me to work on the embassy project, I thought I would just be helping with the technical aspects (drawing, working on the mock-up), not the conceptual ones. Meanwhile, the professor allowed me complete freedom of expression, including in the drawing process – and so we started to work together, in partnership. Towards the end of our work for the competition, the professor told me that I was officially a co-author of this project – I did not expect this, it was a great honour and joy for me. The graphic design was also important in the competition design – we wanted to present our concept in an attractive and effective way. At that time, I was very much into photography, and I had an idea that we should use photographic paper for our presentations, while the drawing on it would be entered through a series of exposures. I decided that we would make the background in a shade of gray, and that the shadows would be black. We made the negative by cutting the form with a razor blade and a knife, then we superimposed this negative on the photographic paper in the darkroom with a red light, and we developed it using different exposure times. In this way we achieved the effect that today is rendered by computer visualization. This manner of presentation contributed to our success in the competition. We also had fantastic collaborators on our team – Andrzej Lorek and Andrzej Gonciarz – who were very supportive in presenting all the technical details of the project.

MK: You won the competition. How was the cooperation with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, how was your first trip to India?

SD: In terms of functionality, the Ministry found our project to their liking. We had a positive trade balance with India at that time, and thus we were able to carry out such an ambitious architectural venture. Ministerial officials practically did not interfere in the project, they only advised us on the procedures of the institution’s functioning: such as security measures, or protection of state secrets. We enjoyed very comfortable working conditions, and we were allowed to apply all the technologies that we had proposed in the project concept. This was also greatly facilitated by the architectural firm Kothari & Associates from New Delhi, who really proved themselves to be excellent partners. It was a large, versatile company, experienced in running large projects from scratch, from the concept stage all the way through to the implementation. Our Indian partners knew a lot of different construction companies, they had the knowledge of the market, which was enormously helpful. We had developed our design for the competition a little bit intuitively, we did not know the local building regulations. The first thing Kothari & Associates did for us was to check that our project complied with the local regulations – and can you imagine we did not have to make any changes! It was truly incredible, because in India, the limits to the building’s height are determined by norms of angular value. The angle from the boundary of the plot determines the possibility of building higher up, depending on the distance to the adjacent buildings. It is a simple and fair solution. In Poland, it is problematic that according to regulations, we are able to build high structures merely 4 metres from the border of the plot. Our New Delhi design also passed muster in other aspects – the building’s location and layout within the plot, the situation of stairwells, etc.

MK: If I understand it correctly, there were no changes to the dimensions of the building’s body, to the structure itself. But did the confrontation with the local conditions on site not require any adjustments or improvements to particular, detailed design solutions?

SD: The only new solution that we introduced was the finish of openwork sun visors protecting the glazed hallways against overheating. During our second or third visit to the site, we tried to design elements of these covers – I thought of a detail that could resemble a plane propeller. I imagined such elements in rotation – I thought that this could be something interesting. We started talking about it and it took us to a turn of a screw, thus creating the idea of a detail, forming openwork breakers of light. The only problem was to position their curvature in a manner that would follow the “scale of the sun,” on the one hand providing the shade, but on the other hand, without blocking the view to the outside.

MK: We also know of this idea from the account by Professor Cęckiewicz who – when visiting New Delhi – tried to defend some design solution against budget cuts by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He said to himself, “They are starting to tighten the screw.” And the word “screw” turned into the idea for the detail.

SD: Yes. From the propeller we went on to the screw. And it was in a shed on site that we started testing the model of this element.

MK: You said that the embassy was to be synonymous with the modernity of the Polish state. How did this correspond to the reality at the construction site in New Delhi? What did the cooperation with the contractors look like?

SD: This modernity was largely an artificial construct. We collaborated with a wonderful engineer, Kazimierz Flaga, who was a consultant on the project from as early as the competition stage. We were aware that one of the most difficult problems of the design would be the nodes at the junction of the support and the slab of the ceiling. Because of the elevation, the raising of the embassy building, it was important not to lay the ducts with the installations from below, in order to hide them. That is why we came up with the H-shaped columns that incorporated enough space for the wires, the drains from the roof, and so on. These columns were meeting with the joists that bore the load of the ceilings. The joists also had to be double, in order to incorporate the installations. Kothari decided, at the stage of technical construction design, to send these structural elements to the engineers at PEC University of Technology in Chandigarh for calculations. And thus the most complicated calculations and conversions of nodes and contractions were conducted in India, based on the initial project concept by engineer Flaga and ourselves.

MW: And what were the biggest difficulties at the design and implementation stage?

SD: During the implementation of the embassy project, I visited New Delhi thirteen times. We usually spent two or three weeks there on each occasion. At the initial design stage, before obtaining the construction permit, we were relying on our own calculations. We had to bring to India a 1:200 scale model, that was a requirement. The model was 200 × 70cm – we had to carry it as cabin luggage. During each flight to India we had one adventure or another; such were the times; but our first journey I remember with particular clarity: we had a stopover in Beirut, where we forgot to switch our watches to the local time, and we missed the plane to Delhi. The trouble was, we did not have any local currency, only 20 US dollars that we had smuggled out; to change our flight booking would have cost five times that amount. We were rescued by the Polish consul from Ankara, who accidentally overheard that our plane had departed an hour before. He came up to us and said, “Gentlemen, I will help you, I know the ambassador in India, we will settle it, I’ll pay.” And that was that. And when we speak of our encounter with India itself, it was fantastic, we experienced a different culture, a different lifestyle. I will never forget it. People were smiling, they were poor but very friendly, open. The India of today has changed a little bit.

MK: Professor Cęckiewicz also emphasized the role of water in the building tradition. The design of the embassy referred to that, by the introduction of a decorative body of water, several dozen metres long.

SD: Unfortunately, due to the cost of maintaining this decorative water feature, this part of the project was later removed. The pool was levelled and a tennis court was built in its place. For me, this is totally wrong – instead of the sound of water, you can hear the “bounce, bounce, bounce” of a tennis ball hitting the concrete. How could they destroy this interior like that? Especially since water, historically, played an important role in Indian buildings, and not only for decoration – in dry seasons, it provided coolness and the much needed humidity. The fact that the pool has disappeared from our project is very sad.

MK: The most famous examples of modernism in this part of the world include Le Corbusier’s Chandigarh and Louis Kahn’s projects: the Institute of Public Administration in Ahmedabad and the parliament building in Dhaka. How were modernist ideas received and adopted in India? Did you have an opportunity to see modernist designs by local architects?

SD: In New Delhi we were primarily looking at the architecture of the embassy district – there were some very interesting solutions. The American Embassy designed by Edward Durell Stone in the early 1950s was excellent. We were impressed by the Embassy of Czechoslovakia – an energy-saving building, hidden underground, a kind of landscape architecture. I also remember the Canadian embassy designed by CP Kukreja Architects – an architectural studio based in New Delhi. Other than that, most of the contemporary urban architecture in India was uninteresting – these were ordinary, plaster-covered houses, often built using DIY methods.

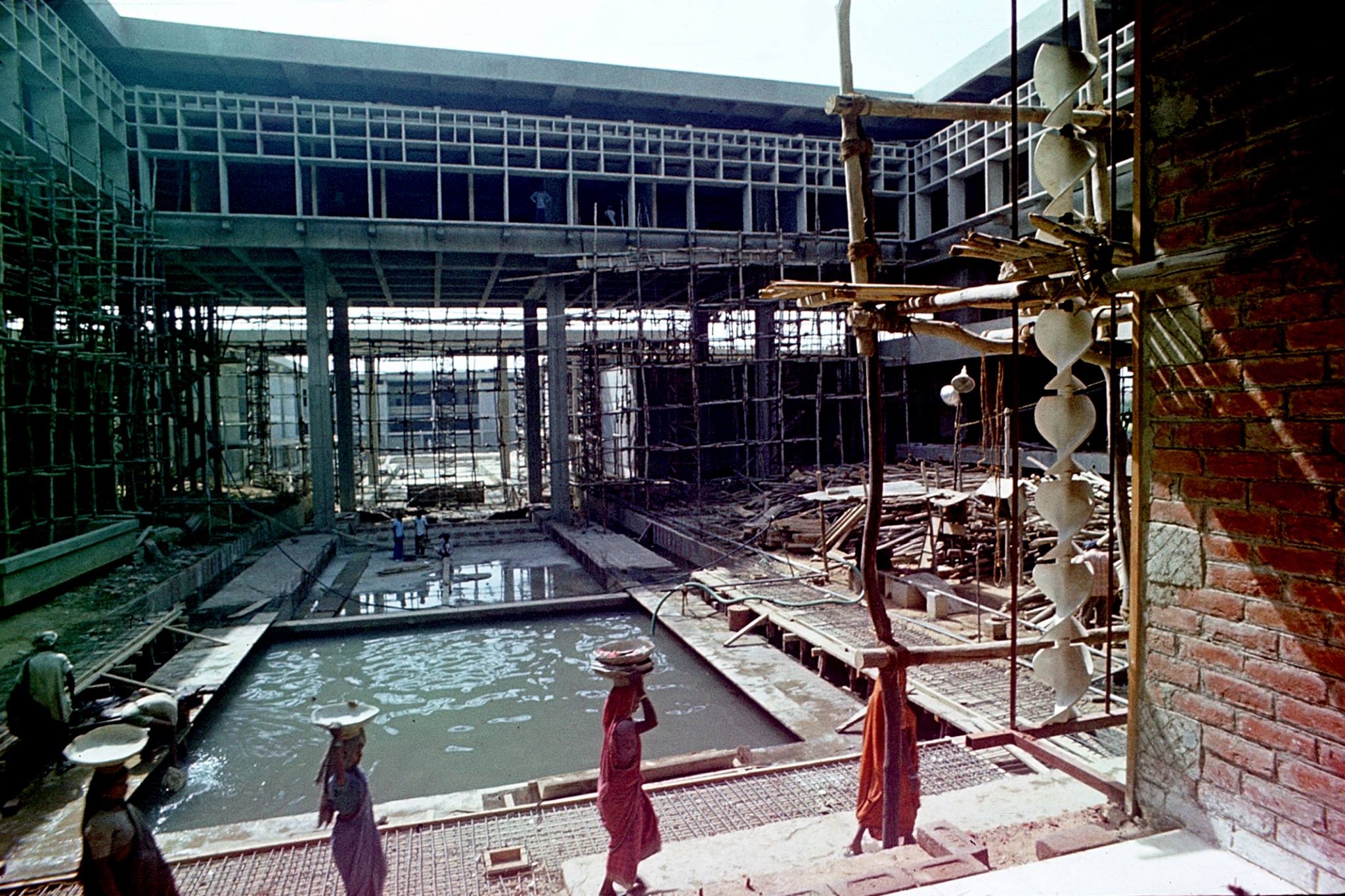

MK: You spoke about the cooperation between Polish and Indian constructors on the embassy project. And yet the building itself was also erected largely by simple craftsmanship – Professor Cęckiewicz’s account shows that local workers, who used the simplest tools, played an important role.

SD: One can make the most of the tools available. A good result can be achieved not only by applying the latest technologies, but also by the work of hands and knowledge. A great influence on the building was the engineer Antoni Kubicki, who was the inspector responsible for investment supervision. He was a man of great charisma who communicated well with both the project team and the simple Hindu workmen. A fantastic character that cemented all relationships. When we first visited the embassy construction site, we saw people with pick axes, splitting the rock, no mechanical diggers – frankly, we were quite bewildered. We have pictures of kids at the construction site – because there were mothers working there, who brought their children to work with them. But when they showed us the first foundations – very precisely cast – we relaxed. Furthermore, Mr. Kubicki told us that one column was demolished because it was inclined by 1 cm at the height of 11 metres. Of course, the Hindus had modern geodetic devices, such as theodolites, so they could check everything – thus, technically, there was no problem here. Most of the work was done by hand though: women transported concrete on their heads in special troughs, men built scaffolding from bamboo that looked like it was about to collapse, but instead it developed into a perfect structure. Local construction methods proved to be reliable – in the role of a carpenter’s level, there was a water hose. We were amazed and impressed with the meticulousness of building supervision: on the one hand, the architects and engineers of Kotarhi controlled the construction process, on the other hand – Mr. Kubicki did, also with a team of local engineers and surveyors.

MW: How did the solutions you proposed pass the test of the Indian climate?

SD: The whole building was designed in such a way that air conditioning would not be necessary. That was the idea, to protect ourselves from the inconveniences of the climate – and to that idea we subordinated various elements of the project, including a large number of pergolas, the introduction of shaded atriums, etc. Raising the building above the ground ensured the flow of air from the bottom and the removal of the ventilated air through the shaft upwards. Both the embassy building and the rest of the premises, such as the residential quarters, were naturally ventilated, which made the use of air conditioning unnecessary for long periods of time. We have been told by the users that our solutions have workedwell.

MK: Finally, I would like to ask you a question about your attitude towards critical regionalism. Can the house you designed in Burów be treated as a kind of declaration on the subject?

SD: Regional form is not a constant, permanent element. New solutions are developing over time, often inspired by users. Something like a native tradition is formed. People identify with these solutions, and by the means thereof, they identify with the place. My project is basically the result of observing the traditional form, of which I speak. It is, in a sense, a synthesis of such factors as scale or proportions, and these form the geometry of the whole body of the structure. This pure geometry was defined by the edges of the planes of the walls and the roof. The use of wood, to the maximum, as the finishing material of these surfaces also results from the continuation of the tradition, in which the matter and the form are its reflections.

Translation from Polish: Dorota Wąsik