Narratives in the history of Újpalota

“The generation who grow up here will surely have bonds with Újpalota. They will have memories.

Our generation of this housing estate is yet without memories.”

Tamás Lipp, Conquest in Újpalota

Újpalota is a housing estate that is symbolic in several ways: following the experimental decade of the 1960s it was the largest industrialised housing programme to date and also the first greenfield development without immediate urban surroundings on the periphery of Budapest. Among its inhabitants, intellectuals were for the first time in the minority compared to workers’ families moving in from substandard tenement blocks and temporary housing barracks. There was also an explicit requirement to design an “urbane” housing estate that went beyond bedroom communities with complex infrastructures of education, health care and services, often exceeding the technological limits of industrialised housing factories. Moreover, this large-scale project has been closely followed since its first steps by in-depth research about the accommodation processes of new settlers, the emergence of communities and their problems. This evolution has been documented through ethnographic methods, interviews and sociographical analysis until the changes of 1989 and the subsequent period up to today.

The viewpoints provided by past and contemporary sources help to construct insider and outsider descriptions of the housing estate as well as the process in which these changing and often conflicting perspectives and value sets competed and interfered in shaping the images and understanding of Újpalota. My questions intend to investigate the shared frameworks that evolved during the 42-year history of Újpalota and which could provide a basis for future generations’ identities, as well as the degree to which these frameworks could be relevant for other housing estates. The changes of the following decades have overwritten the narrative of foundingas- conquest in several ways, and I believe that following these enables us to extend the analysis of the housing estate as a cultural phenomenon and understand some of its future potential too.

Beyond bedroom communities

The Újpalota housing estate is one of the first housing projects in Hungary that was a greenfield development on previously unbuilt land. The planning process was led by Tibor Tenke, starting in 1964 in the Institute for Typological Planning, and construction started in 1969. The plans followed the principles of the 15-year housing programme and its prescribed numbers on apartments and services with the involvement of the Budapest Housing Plant No. 3.1 At the same time, however, it was an explicit goal to prove that prefabricated housing technologies are capable of creating a colourful and diverse urban environment. The importance of this issue was probably due to the insulated, peripheral nature of the site which lacked urban surroundings (it was originally designated as forested land in the city’s General Development Plan) and partly to the rigid architecture of the otherwise popular housing programmes of the previous decade.[ This turn, however, also marks the beginning of the era when the industry’s priorities gradually overrode all aspects of urban planning and architectural design in the following decade – Újpalota provided a preview of the coming changes and the compromises between the design and the built results became integral, defining elements of the community’s life and self-image.

The master plans developed under the direction of Tibor Tenke and Árpád Mester show the influence of Team 10’s contextual critique of modernist planning. Services and commerce are organised along promenade-like axes with separate traffic lanes and multiple types and scales of housing which create a diverse system and an overall unified profile.3 In an interview by Tamás Lipp4 after the completion in 1977, Tenke was asked not only about his original ideas, but also about their realisation and afterlife. The promenades along the axes were significantly transformed – the original scheme of vertically separated traffic lanes was cancelled and the commercial zones at street level were also replaced by apartments. The schools and public facilities of the low-rise sub-centres behind the multilane promenades and their high-rise buildings were partly built, but the culture hall and community centre, providing the effective centre of the housing estate, were entirely missing. The sole construction of the centre was an 18-storey housing tower with a water tower on top, which due to its height and unique shape, differing from factory-built units, instantly became a sort of symbol of the housing estate.

However, the architects participating in the design of Újpalota and its environment described the process as liberating and creative, taking place in the foreground of the New Economic Mechanism, highlighting the diverse use of industrialised housing technologies and especially non-standard solutions.5 The uniqueness of the housing tower for instance also materialised in its structural constraints (monolithic concrete due to the weight of the water tower) – and it seems almost symbolic that even Tenke, despite all his requests, could never get an apartment in the building.

What, then, was the sort of utopia that Újpalota presented? Post-war planning and its faith in technology led to a peculiar loss of meaning in architectural forms: diverse spatial structures created as assemblies of identical or similar elements, especially if they lacked public functions, ultimately always represented the same function. The scale of architecture faded out between urban and interior spaces, only maintained by the grid of prefabricated elements and by community life which was forced to operate in open spaces. An architect who moved to the housing estate saw this to symbolise the permanence of compromises: the interviews of 1978 contained both the basic themes of criticism (monotony, unfinishedness) and the appraisal of the plan’s virtues, taking a kind of anticipatory position with regard to the future of Újpalota.

Spatial stories

The lack of public facilities and the monotony of industrialised architecture are present all the way through the following decades, as the efforts and goals of civil society and local anecdotes narrating the environment both use these two themes as their basis. It is also remarkable that the interpretations of key topics such as alienation, monotony, apartment sizes and the uses or status of public spaces always change and occasionally even contradict each other.

The use and enrichment of the tabula rasa urban environment through linguistic tools and imprints of memories starts with moving in, for individuals and communities alike. The word “conquest” which appears in the title of a 1978 sociography symbolises the founding act of the first-generation communities, also remembered in several interviews. From 1971 onwards the sense of belonging and shared experience among the migrants to the housing estate, both physically and metaphorically incomplete, was embodied by moving in and bringing the apartments to an acceptable level.6

The lack of spaces designated for community life had consequences from the very beginning. As cultural life had to be based on local private action, the norms that emerged for organising culture have regularly highlighted the tensions between civil initiatives and narratives of power. On the other hand, initiatives such as clubs, apartment-nurseries or the Újpalota Szabadid Központ (Újpalota Recreational Centre), which operated from 1977 without a venue, were extraordinarily adept at using the institutional and open-air spaces of the housing estate on a temporary basis, also forming a network of regular collaborations among diverse organisations.7 These events provided their new venues with meanings and interpretations, consequently establishing tools for expressing individual and shared identities in the public space and quickly accumulating a local mental geography of users besides the bird’s-eye perspective of the planners.8

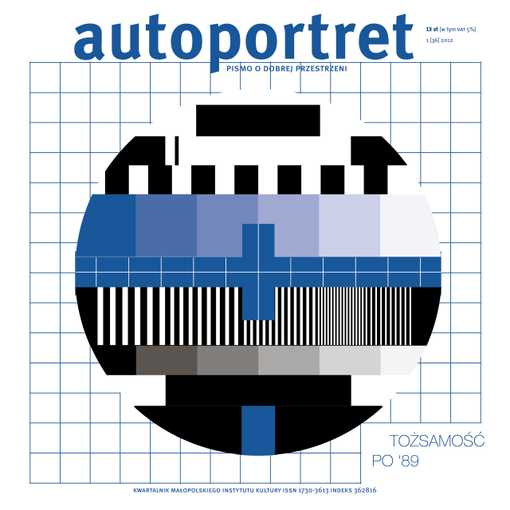

Such roles of narratives associated with spaces can be read from the histories of street names. There are multiple versions about the dates – some first-generation stories are taking place on nameless streets, despite the fact that the choice of names which also connect to local history is linked to a television quiz show that was airing at the time when construction began in Újpalota.9 The local history quiz show entitled Black-White Yes-No featured teams from Óbuda and Rákospalota, and the latter, in preparation for the second round after winning, prepared an in-depth study of the district, listing, among others, the old names of roads and vineyards from vintage maps that eventually provided the street names of the housing estate.

This is how the metaphorical-historical and actual discovery of spaces is transformed into spatial narratives. The same process can be seen in another dimension in the youth novels of Mihály Padisák which take place in Újpalota, where kids moving to the housing estate become explorers of “Indian” tribes and public spaces and construction sites become their unconquered hunting territory.10 That this was an actual pastime activity is revealed by the works of Balázs Beöthy. This artist, who spent his childhood in Újpalota, reconstructed the layers of meanings they had created over the area in a 2006 installation entitled In search of the spiral.11 The piece involves his childhood companion of “Indian” games, juxtaposing their experiences from movies and fiction with texts on critical social theory secretly written at home by his father and the context of the housing estate which inspired and contained both activities. An earlier photo installation, entitled This song means nothing, creates an audiovisual environment in which the Wild West romanticism of Native American movies meets the Wild East environment of Eastern European housing estates, and narratives of heroism and wayfinding in the wilderness rewrite the landscape which opens up from the high-rise rooftops.

The territorial fight for public space is reflected in the relationship of political power and services without venues, decentralising their operations. While Újpalota had 60,000 inhabitants at its demographic peak, several basic services such as medical or childcare facilities had to find informal solutions to operate (i.e. working out of apartments). Groups of youths lacking clubs and spending time on streets and squares quickly became the source of numerous conflicts that went beyond police and social policy issues and also affected the dynamics of conquest in the developing “Újpalota identity”. Architects refused ideas to convert unused spaces by staircases into clubs on the grounds explained earlier, but the existence of uncontrolled social organisations concerned party officials as well. Street gangs in the neighbouring Rákospalota reasoned that the behaviour of their Újpalota counterparts was explainable by the lack of street codes they themselves adhered to, which could also be seen as a civil reflection of the political rivalry playing out on the district level. Rákospalota, which had grown from a village into an underdeveloped town, was competing for resources with the “modern” and much larger Újpalota, which on the other hand lacked infrastructure and political power in decision making. Outside viewers often living in significantly worse apartments found it hard to accept the growing demands of the inhabitants of new housing estates, while from this perspective they seemed arid, monofunctional and uninteresting as urban environments.

The reason behind the founding of the Újpalota Recreational Centre was partly to mediate this situation and to fill the void with schemes. Its three decades of operation could also be described as the continuous reinterpretation of the spaces of the housing estate:12 the programmes organised for the first Újpalota Days in 1978 are key elements of the local folklore to this day. A concert by the band Piramis on the rooftop of the kindergarten, tower music in the tower house as well as chamber music events and a free annual open-air iceskating rink worked as a détournement opening up not only public spaces but buildings and interiors as well for free association – as long as they stayed within the limits of cultural politics.

The strained relationship of the municipality and the organisation clearly appears in the management of participatory projects and the communication of development concepts. The main square, currently a park, originally the site of the Cultural Centre, was the object of several debates regarding the proposed new cultural and community functions, with much criticism going towards the programme, the proposed site of a new church and the intransparency of the design process. A former Party office building had been host to cultural schemes even before 1990, and since then it has been used as a community hall operated by the Újpalota Recreation Centre.

New public spaces have been created in the environs of the housing estate by a church built in 2008 on an adjacent site and by one of the flagship commercial developments of the transitional era, the Pólus Centre shopping mall. The small forested area once occupied by “Indians” and later used as recreational park, its neighbouring allotment gardens and the adjacent shopping mall with its sister Asia Centre fulfil most needs for commercial and other services, somewhat overwriting the original urban layout of Újpalota. The central promenade designed by Tibor Tenke is still unbuilt and empty, except for the tower block in the middle and the market hall and the main square with its transit hub and cultural venue at each end.

The symbolic central role of the main square is reinforced by the foundation stone located here and a sculpture donated by the twin towns movement of the 1980s. These, the later erected memorial of Tenke and the most recent fountain lead the viewer back to the stories constructing and connecting young towns. The first movers live in a strong community made of personal stories and memories where the creation of the urban context lives as a direct experience. The fragile process which might elevate these from a personal dimension to a shared knowledge of the community that can pass on to latecomers and today’s generations can be understood on the main square. The sculpture donated by Ózd is supposed to symbolically fill the void of the missing cultural centre, but the piece depicting the unity of the capital’s districts, also known as Three-legged Lizzy, does not seem to withstand the passage of time in either its forms or in its material.13 It has nevertheless become a fixture of the square, partly since it was built upon the foundation stone, so much so that a 2011 design competition for the new main square required that it remain untouched – contrary to the memorial to Tibor Tenke, which can be freely moved around. A less directly legible but much more personal and dramatic memorial, connected to the construction of the housing estate, has recently disappeared from the square. The housing block on the Nyírpalota street side was also known as The block with the black attic, since its unique black top panels commemorated a young construction worker who had fallen off the scaffolding during a night shift.14 That is, until its façade renovation. The newly insulated building was painted with abstract geometric patterns that have no relation to any locality; their main role is to break down the scale of the façade into smaller units after the original panel grid patterns disappeared. I find the block with the black attic’s case an inspiring example of public art reflecting on the discursivity and sharing of memories. In order to keep the heritage of the first generations functional and transmissible, the renewal of squares and façades needs to focus on the archaeology of stories native to Újpalota.

Apartment by apartment

Working to improve unfinished, deficient apartments as a force that creates communities is a key element of several reminiscences, just as the shock of change in lifestyle for the workers who arrived in masses for the first time.15 For those moving in from transitional housing, dilapidated sublets, store-front apartments or shared units the first experiences of spaciousness are instantly followed by the often emotionally and culturally extreme challenges of settling in, furnishing and maintaining a place called home. Apartments of relatively larger sizes were often inhabited by multi-generation families where high occupation densities led to inevitable conflicts. It is remarkable, though, how previous living conditions and the frustrations of new apartments are juxtaposed in the interviews. Schematic floor plans, overcrowded living and nosy neighbours knowing everything about everyone appear in a neutral or nostalgic tone in remembering eclectic tenement blocks, whereas in the case of the housing estate their perception is clearly negative. The shifting scales probably affected the scales of communities and spatial structures as well beyond the personal environment, as several former neighbours moving in together reported fading friendships and isolation as families gradually turned inwards. This process was enhanced not only by the often-mentioned lack or uselessness of semi-private zones, but also by social factors such as the embarrassment of having to take off shoes on carpet flooring.

The patterns of alienation were likely different in each building and staircase unit – younger children who grew up here remembered staircases as “the basic units of community life” with open and traversable apartments, possibly much more so for children than for adults.

The dissolution and gradual silence of the first settler communities coincided with the wearing out of the increasingly hopeless battle for public spaces as well as the unfolding of the culture shock of migration and the economic recession of the 1980s. The detailed sociological surveys of 1978 and 1985 predicted the demographic trends further accelerated by the later political transitions in which the number of inhabitants dropped to 40,000, dominated by elderly, single, poorly educated and impoverishing households. Community organisations have consequently shifted the focus of their activities to maintaining social services and programmes which serve techniques of survival beyond cultural content.

Private spaces appear in the life of the community through their owners, too. Although Újpalota was never considered an elite housing estate, public personalities or otherwise noteworthy characters moving here became important elements on the cultural map of the neighbourhood. The artist studio apartments, for instance, which were built on top of the tower block as a result of tough local lobbying through political connections, explicitly used the artists living there and their ties to the community as a communication tool.

The local history volume by Erika Szepes is, however, strongly critical towards opinions stressing alienation and the dissolution of communities as dominant trends. Her text, beyond being a personal testimony, sees the changes of 1990 and the radical transformation of financial situations as the main influences on turning inwards, but she clearly puts the power of decade-long neighbourly relationships above this. A critical perspective is also developed on the allegedly identicallooking apartments forcing their inhabitants to perform the same movements and actions in all buildings, offering a slideshow tour of apartments with occupants of different backgrounds, showing how their similar beginnings three decades before led to completely personal and unique careers and environments.

Conclusion

The image of a housing estate is created not only by the buildings (or the lack thereof) and the seemingly clear slate provided by the architects, but rather by the set of possibilities and constraints as well as coded meanings embedded in the plans and the evolving lives of their inhabitants. This situation, fragile and uncertain compared to the historical city, has spawned a set of negative images about housing estates, the narrow horizons they offer for living, the lifestyles of poorly educated inhabitants and the architectural language associated with totalitarian regimes.

In the case of Újpalota I see a mixture of concepts much more open and traversable than elsewhere, visions on the possibility of change and getting things done, and an environment with tight constraints for the entrepreneurial spirit. The young age of housing estates, their abundance of spaces and dilapidated greenery, hold the promise of much more radical transformation beyond the immediate need for renewal than the traditional city.

A new development programme launched in 2011 through competitions and interventions sets out with goals of stability instead of temporality, career paths instead of survival and cooperation with civil society to renew the public spaces of Újpalota and its communities that reach the size of the city of Eger. The brochure, which adapts green city policies to the special needs to housing estates, offers a vision of these structures as laboratories of green innovation and lifestyles based on flexible work.16

In order to avoid another tabula rasa situation, it would be of critical importance to uncover potentials now relegated to the background, like the shared optimism of the founding period or the personal memories and traces of forty years, and treat the housing estate as a surface where these can appear and become tools of continuity, which is the basis of all urban history.