‘[…] how come that, born out of chaos, we are unable to face it ever again; we look and in our eyes

order… and shape are born”.

Witold Gombrowicz, Kosmos

The educational offer of the Urbino Academy of Fine Arts as described in the academy information brochure covers a full range of professional stage qualifications, including knowledge, competences and skills. What the brochure does not refer to, or at least not directly, is information about real opportunities to experiment with and imagine not only a theatre space but also the whole world hidden behind it. The stage design school auditorium contains not only designing tables and computers, coloured pencils and video projectors but also electric saws and all sorts of tools. In this way background painting, costume sewing, sculpting or lighting design are of equal importance in the stage design workroom. It is also why studies of Claudio Monteverdi’s 1608 opera Il ballo delle ingrate (The Ballo of the Ungrateful Ladies)1 and an essay by Jean Baudrillard titled Impossible Exchange (1999) inspired an academy graduate to write a theatrical play Senza fin.e (End.less).

A close relationship between Monteverdi’s opera and Baudrillard’s essay, on which visualisations of settings and scenes outlined in the play are based and which is analysed in classes offered by the Academy, was discovered by observing that exchange between the reality of daily life and the virtual dimension, where transfer of money, information and all sorts of communications takes place, is essentially impossible. Monteverdi was forced to choose an authentic non-setting for his opera; Baudrillard proves the impossibility of escape to other dimensions of reality or of other potential meanings. ‘The sphere of the real is in itself no longer exchangeable for the sphere of the sign. As with floating currencies, the relationship between the two is growing undecidable, and the rate at which they exchange increasingly random. […] Reality is growing increasingly technical and efficient; everything that can be done is being done, though without any longer meaning anything’2 . Depletion of meanings entails an uncontrolled proliferation of markers since places that seem to be real are in fact totally conditioned by signs and symbols which are no longer comprehensible: every day someone devalues our economy, and lends or withdraws credibility to a given company without a sensible justification. Motivations given today will be different tomorrow so it is impossible to distinguish between cause and effect, or to understand if it is really the end of the world as we have known it, or perhaps another worn-out forecast of the same, forever postponed, apocalypse. The starting point for Erica Montorsi’s theatrical play is the condition of young people to whom all opportunities seem to be inaccessible even before they could try: with no work, no prospects, they are blamed for ‘a lack of experience’ and reminded that crisis entails forced prolongation of youth, and hence it is an endless and pointless wait. ‘An attempt to give words my bit of meaning’, says Erica Montorsi, ‘proved unquestionably, at least to me, how important it was to follow the ambiguous nature of the »text«. Writing can gravitate towards description or copying, a tendency I have opposed in an attempt to avoid an abyss of the ending and a static meaning. Generally speaking, I struggled with a very human impulse to start from conclusions and to seek places where I should only eventually get; I forced myself to do so in order to abandon any ways or choices that would lead to a straightforward and definite end, choices that appealed to me with an aura of very reassuring solidity – and yet left me unsatisfied. Very soon the exercise brought me relief which I found inexplicable. It seemed fundamental to keep asking questions and to retain the state of »ambiguity«, which permeated the whole process and seemed to be the very essence of pursuit’.

School usually finishes here: it passes on knowledge, and checks whether skills have been acquired and targets accomplished. The Academy of Fine Arts is unique in that the process does not end there; in the school of stage design all assignments (models, drawings and video screenings) must be realized on stage. Chaos in the world should be put in order in the theatre: all details, including scale drawings of scenes, objects and video screenings, must be assessed and realized on stage. ‘The play tells a story of death. The deceased appears on stage in a strange coffin. Poor Enrico Rimasto (literally, the One Left),’ Francesco Calcagnini, senior lecturer in stage design, comments on the staging of Senza fin.e, ‘faces the bureaucracy of the end. It is a comic tragedy where the wrongly deceased is bombarded with questions by three suspicious individuals who, as we learn from the brochure, are examiners. The first examiner is a young woman in a red coat. She has two black holes for eyes; perhaps she is blind as she moves hesitantly, like a sightless person. She welcomes poor Rimasto cordially, stroking him almost like a lover, before she heaps on him a set of formalities that are allegedly indispensable to certify the »deadness« that he acquired through his demise. Amid explanations, certificates with stamp duty paid and other documents, the spectator realizes that a cat must have precipitated or even caused the tragedy but the dynamics of the event do not seem to be of importance. A silent, giant plush he-cat appears on stage, as an enormous caricature of the unexpected procedure. If the first examiner spoke in the language of official forms, the second scene is saturated with all sorts of TV buzzwords whose meaning is hybridized. In this way a whole series of replete, nauseating double meanings emerges’.

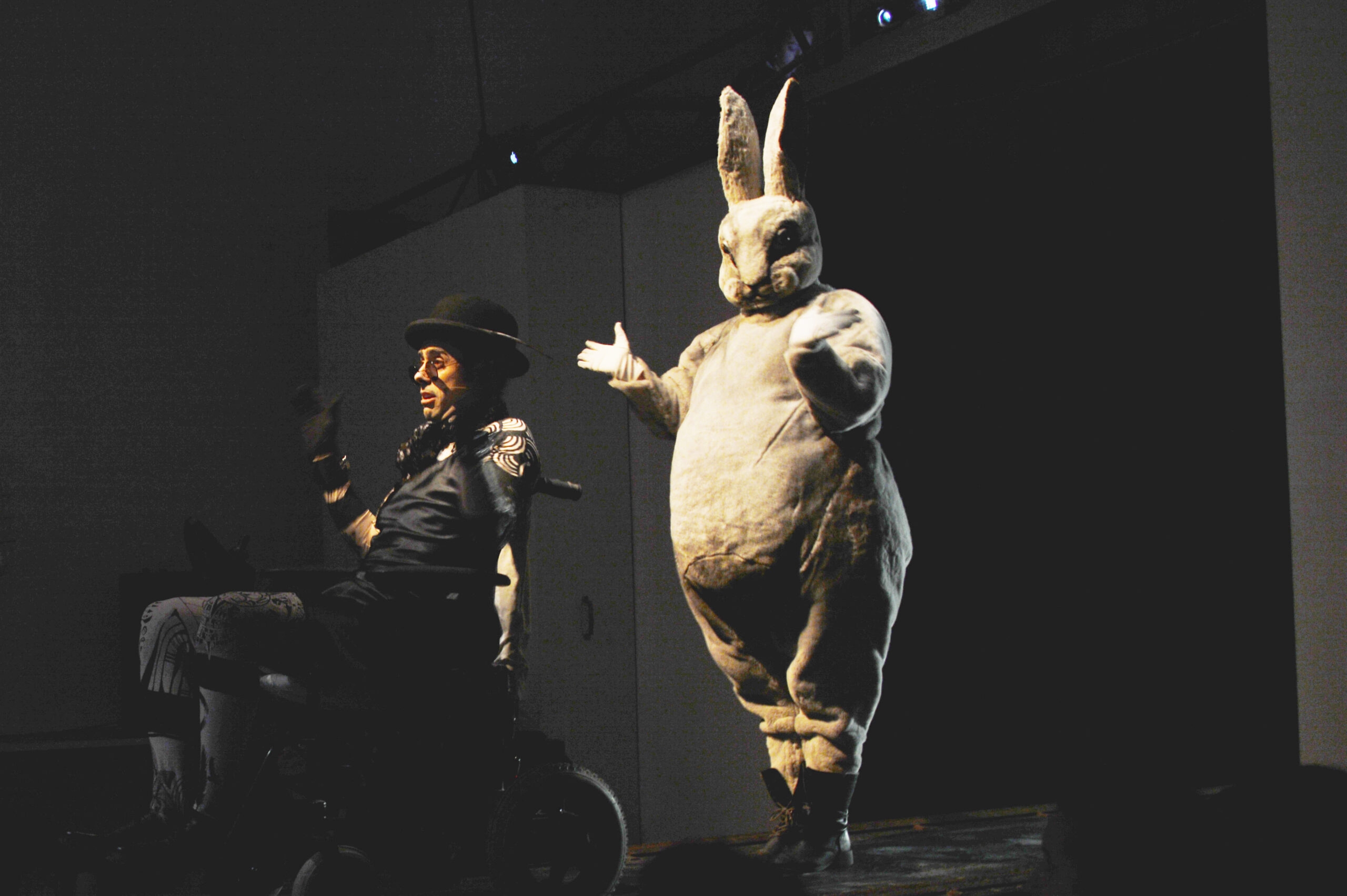

The third scene features a wheelchair-bound disabled man with tattoos all over his body; he claims to care at all for Enrico Rimasto’s fate, thus sentencing him to an eternal present and an endless wait.

Spatial design in the play features the theatre auditorium divided into two sections with a long, narrow platform resembling a catwalk, fully covered with old, dirty and dusty school blackboards. The curtains that reveal and conceal the stage space are two transparent sheets of foil, like specters. A notable aspect is that the project is realised at practically zero cost. Due to cooperation between the Academy of Fine Arts and the Rossini Opera Festival, the school of stage design carefully preserves and utilizes all leftover, discarded materials used to stage operas for the international Gioacchino Rossini festival. The cooperation was sanctioned with a convention based on which Academy students created stage design for the operas Demetrio e Polibio in the 2010 season and Il signor Bruschino in 2012. ‘The formula has never been applied automatically’, says Francesco Calcagnini, ‘but based on the principle of healthy alternation. It makes me think that our contribution is not determined by the fixed dates in the festival calendar but that we are always intentionally invited to participate in given projects. Stage production for the Rossini festival certainly contributes to teaching because students perceive an increasingly close relationship between the world of education and the world of work’. It should be added here that the art of recycling is not only a noble ecological practice but, first and foremost, a genuine challenge for imagination and creativity, which, contrary to popular belief, should not be regarded as a sort of godsend or talent acquired by peculiar recombination of genetic codes; creativity stems from daily practice and continuous work on the project. It is not accidental that a play narrating tragicomic challenges that the not-fully-deceased has to face was realized with materials recycled in the school workroom, materials that were processed, repainted and radically transformed on school desks and tables. The eventual production in the school auditorium closes with the sounds of Leonard Cohen’s The Future, thus characterizing the generation for whom the idea of sustainable development is not a choice but a necessity. There are no grounds for despair but one should realize that creativity does not result from quality or an abundance of means and instruments; it results from an ability to constantly rethink the world, to restore its form and order which, ultimately, exist only in our eyes.

Translated from Italian into Polish by

Emiliano Ranocchi

English translation

by Anna Mirosławska-Olszewska