In late February 2020, Bratislava is covered in posters of smiling men and women. Under the monumental SNP Bridge, only a few metres from the Holocaust Memorial, hangs a poster belonging to the nationalist SNS party, bearing an eagle and a promise to free mothers from tax. Next, there is a politician surrounded by several women. To avoid misunderstandings, each of them has an inscription indicating whether she is a wife or daughter. The parliamentary election campaign is reaching its peak in the Slovak capital, and, perhaps for the first time since 1989, housing policy is an important issue. This is a sign that the housing crisis also concerns Slovakia, and that here too, the limits of the neoliberal approach to housing are becoming all too obvious.

A country saddled with debt

“The topic of housing is migrating from expert circles – where it was, of course, always discussed on both the national and international level – into political debate. This can be a good thing or a bad thing,” says the leading Slovak expert on housing Elena Szolgayová, former director for housing policy and its instruments at the Ministry of Transport and Construction.[1] “The tragedy of housing policy is that any good solutions begin working after six or seven years at the earliest. What we need are long-term, constructive, and fully conceptualised activities in order to do something worthwhile instead of racing from one end to the other,” explains Szolgayová, who helped write the Geneva UN Charter on Sustainable Housing and the 2016 Urban Agenda for the EU, and was, until last year, chair of the Committee for Housing and Land Management of the UN Economic Commission for Europe.

All parties mentioned housing in their election programmes, at least in passing. More accessible housing could mitigate citizens’ indebtedness, which is the worst in all of Central Europe in Slovakia. According to Miriam Kanioková and Sergej Kára, who curated the Bývanie je (nám) drahé (Housing – Dear) exhibition,[2] almost every fourth adult in Slovakia is under distraint. The Slovaks owe their banks thirty-two billion euros, and housing loans represent a significant portion of this number.

Compared to other election topics, however, housing was nevertheless in the background. Almost ninety-one per cent of Slovaks live in housing they own (compared to about eighty per cent in the Czech Republic), so a large part of the population has not yet felt the effects of the housing crisis first hand. This problem disproportionately affects inhabitants of large cities (particularly Bratislava) and the younger generation, which, naturally, wants to acquire independence. For these groups, as well as for groups at risk economically and socially, the insufficient number of financially available apartments (whether for sale or rent) is crucial.

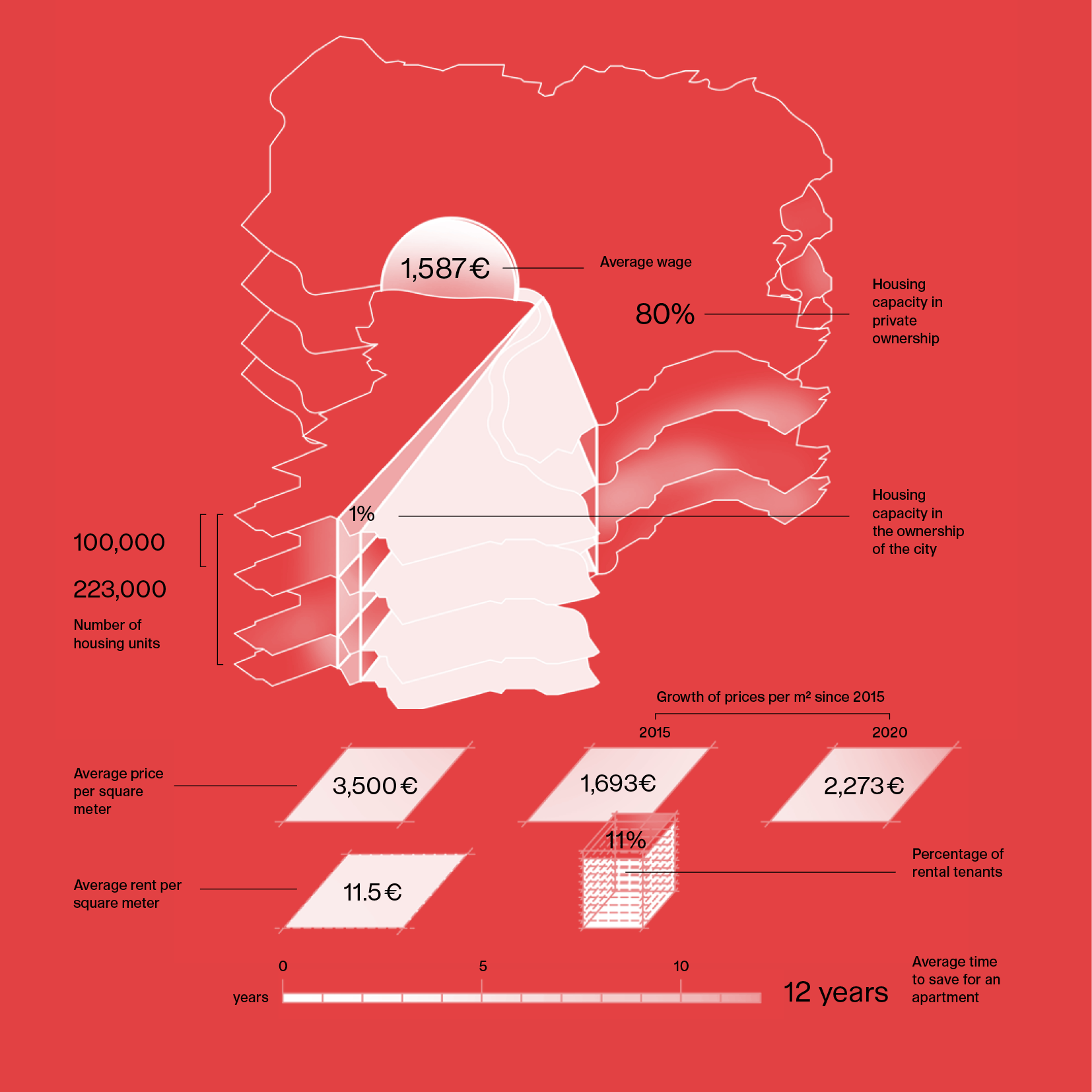

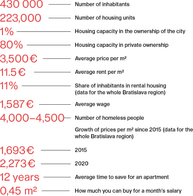

The situation is most dire in the capital, where, just like in other European cities, the prices of real estate and rent have grown quickly in the last few years. Last year, they surmounted the previous record, from just before the 2008 economic crisis. This growth wasn’t slowed even by the coronavirus epidemic – though the real estate market seemed to stop for a moment in April, it began a process of renewal as early as May, so the second quarter displayed a growth of one and a half per cent compared to the first. This July, the average price of the apartments on offer rose to a record 3,500 euros per square metre, signifying a yearly increase of 17 per cent, as reported by Bencont Investments in their regular market analysis.[3]

No parents, please!

The average price of rent has decreased slightly since 2019, when it reached a peak of 12.3 euros per m2 per month. Unlike Prague, where the price drop in 2020 was mostly related to a decrease in short-term rent, Bratislava’s decline is related to fewer apartments being built in newly built properties, where rents are generally higher. Prices per square metre are therefore between 11.5 and 12 euros in both cities.

In Slovakia, as in other countries in Central and Eastern Europe, rental housing is considered a temporary solution to a personal emergency. Even in the Bratislava Region, where the ratio of people renting accommodation is the highest in all of Slovakia, only around 11 per cent of the population pay rent.

Generally, however, rent prices have gone up in previous years (some ten to fifteen per cent between 2018 and 2019), and, according to the experts, will continue rising.

Many people living in Bratislava are therefore caught in a difficult situation – there aren’t enough free apartments, prices are extortionate, so one must take on considerable debt in order to buy an apartment, and many people will not be given mortgages and other loans. There are also insufficient rental apartments and rent prices are going up just as quickly. “If demand is higher than supply, landlords can begin to choose,” notes Sergej Kára, plenipotentiary of the mayor for social housing and people experiencing homelessness. “And I’m not talking about skin colour, that’s a topic in itself. Discrimination of this kind affects parents, particularly single parents, as landlords will opt for someone less economically risky.” A single parent of one child who works in a chain store is left with only eight euro a day after paying average commercial rent, as Kára and his colleagues demonstrated at the exhibition mentioned above. It is a straightforward deduction that if people spend most of their income on housing – and this is the case for an enormous number of people in Slovakia – they are all the more threatened by losing their accommodation in any exceptional circumstances.

Recently, the media have paid considerable attention to the dismal situation in Bratislava. Just like in the Czech Republic, the reports often claim that the high prices are a result of the small number of apartments available and the slow bureaucratic process accompanying development. Developers continue claiming that if they could build without regulations, prices would “naturally” go down.

Representatives of the city – including Sergej Kára – agree that there really aren’t enough apartments and that the permission process on the level of the city and its individual districts is extremely slow. However, merely speeding them up will not bring prices down. Terms such as “financialisation” and “investment housing” appear minimally in the Slovak public debate, and yet they have a crucial influence on housing, as demonstrated in the introductory text to this series. The global context is thus virtually absent from the Slovak debate, as is the local context. And in Bratislava, local conditions have a determining influence on housing costs.

Municipal apartments? One per cent of the market

“Since 1994, the city of Bratislava has let go some 67,000 apartments. We currently have less than two thousand housing units at our disposal,” explains Kára. About a thousand apartments are administered directly by the city hall and the rest is in the care of various city districts.

This means the city owns only one per cent of all the apartments in Bratislava, and is therefore essentially incapable of exerting any influence on rent prices. For comparison: in Vienna, the figure is 60 per cent, in Brno, 15 per cent, and in Prague, only 5 per cent. If the Slovak metropolis hadn’t sold off its assets, it would now be able to influence rent prices in almost a third of all the apartments in the city.

The city’s housing stock is an important instrument for maintaining an acceptable price range and thus keeping the city socially diverse and functional. If the city has no such tool at its disposal, it becomes much more difficult to maintain even the previously stable middle class, as well as helping poorer classes, people in housing need, or people experiencing homelessness. “The city should own not only apartments for single parents, older people, or people in need, but also for necessary professions such as teachers and social workers,” thinks Lucia Stasselová (SPOLU), deputy of the mayor for social issues. “Bratislava does not have enough of these people, simply because they struggle so much to find accommodation and keep it,” she adds.

A lack of apartments everywhere

Bratislava is no exception in Slovakia. The privatisation and selling off of property took place on a much more massive scale than in the Czech Republic, and there are even cities like Žilina, which disposed of absolutely all of its apartments. And, bar exceptions, no new municipal housing was built. There are also many cases of cities keeping part of their housing stock but not using or caring for the apartments. In recent years, with the onset of the global housing crisis, however, cities are realising more and more that they need their own housing stock.

Bratislava’s current liberal government, led by the architect Matúš Vallo since the 2018 communal election, wants to reverse the trend of selling off municipal property. Vallo’s bid for mayor was portrayed as a civic candidate leading a team of experts called Team Vallo – who prepared an ambitious vision for the general development of the metropolis, Plán Bratislava –, with the support of the centrist liberal movement Progresívne Slovensko (Progressive Slovakia) and the liberal-conservative party SPOLU (TOGETHER). The ruling coalition wants to extend the urban housing capacity in several ways. “We’ve got our eye on some unused properties belonging to the city that could be renovated and transformed into rental housing,” explains Lucia Stasselová. “We’re also negotiating with state institutions and the Bratislava Region, who have empty buildings in the city, about transferring or buying these properties,” continues the deputy. According to Stasselová, this could lead to the acquisition of up to two hundred apartments.

Most importantly, the municipal authorities are restarting construction after years of inactivity. In addition to the reasons listed above, there is a further motivation: the law on restitutions. In buildings that were returned to their original owners after the collapse of the communist regime in 1989, rent is regulated and the city has to compensate the difference between the regulated rent and market-value rent. This costs the city two million euro every year. Furthermore, the law states that the city is obliged to find substitute rental apartments for about five hundred tenants in restituted houses.

Not in my backyard!

Seen from the castle view, Bratislava looks a little like a city put together by children at an architecture workshop looking to test out all the approaches that took place in various European cities over the preceding centuries. In the 1970s, the old town, with its crooked paths and cathedral, was ripped apart by the huge arterial road and the SNP Bridge, crowned by the iconic UFO building. The distant horizon is lined by wind turbines and the chimneys of old gasworks.

However, we need only to turn our heads slightly and we’ll see an unlikely view: directly in the historical centre are several skyscrapers, towering dozens of metres into the air as consumerist counterweights to the Cathedral of St Martin. This is the New Bratislava – the Bratislava of the future. At least according to its creators, who would very much like to multiply the numbers of cathedrals of unbridled capitalism. There must be at least some truth to the saying going around the city – Bratislava today, apparently, is a “Klondike for developers”.

Behind the SNP Bridge is a different “city of tomorrow” – that of the 1970s. The largest housing estate in Central Europe, Petržalka, is home to almost a quarter of all the inhabitants of Bratislava. It is here that the city hall has selected several properties on which new rental houses could be built. But the city’s problem is that it disposed of its best properties along with its apartments during the transformation period and it only has small plots of land left. “But perhaps this isn’t such a bad thing – smaller projects will be easier to accept for the local inhabitants,” thinks Stasselová. In Bratislava too, the slogan “not in my backyard” is important – locals are usually not very happy with the idea of rental housing in their neighbourhood. “People usually support the construction of new municipal housing – anywhere except near their home,” agrees Stasselová. The city hall is therefore organising participative meetings in selected localities, and, according to Stasselová, they have been successful in convincing the inhabitants of neighbouring properties that municipal apartments will not be detrimental to their quality of life. A distaste for municipal development is also rooted in the stereotypes about rental housing mentioned above. “People often think that problematic individuals will inhabit these houses. Though a few apartments will be set apart for people in greatest need, most of them will be aimed at young families, seniors, nurses, policemen, and the like,” explains the mayor’s deputy.

The most developed project so far is a group of houses on the opposite end of the city, in Terchovská Street in the district of Ružinov. The city organised an architectural competition along with the Metropolitan Institute, established in April 2019. The Czech studio The Büro won the commission and negotiations about the contract are currently taking place. Here too, the locals were worried at first, but Stasselová claims they have mostly been assuaged. “At the participative meetings, we don’t just discuss the new constructions but also other problems worrying the locals that we try to address,” she describes the city’s strategy.

The city hall also wants to acquire new apartments through collaboration with developers. It is planning to make use of the fact that developers often circumvented the territorial plan, for instance by bypassing housing coefficients. “They built more housing units that was permitted in the given area, bypassing the regulations by presenting part of the flats as suites, counting these into the category of public amenities,” explains Stasselová. The city hall has put an end to this practice and is negotiating with developers: the plan is that the city will retroactively change these coefficients, the developer will then be allowed to build more apartments, but part of these will be sold off to the city at cost value. Stasselová claims at least some developers are open to this kind of cooperation.

We have regulations, but they don’t correspond to our needs

“At present, Bratislava only has threatened, more threatened, and the most threatened,” says Sergej Kára about the present situation on the Bratislava housing market. “Even the middle class is now among the threatened. It is unrealistic for Bratislava to provide housing for all those who need it in the following, say, ten years,” he responds when we asked him who should be selected to inhabit the new municipal apartments. The current waiting time is four to seven years. “If someone finds themselves in a difficult situation, God forbid a critical one, they have no chance to get an apartment regardless of whether they conform to the current criteria or not.” The regulations for distributing municipal apartments date back to 2000 and they do not correspond to the needs of today. In 2020, however, the system by which apartments are allocated should have been reset.[4]

Before working at the city hall, Kára worked as a social field worker and co-founded the Vagus civic initiative, aiming to help people experiencing homelessness. Socially endangered groups are also his area of expertise at the city hall. These groups are not eligible for housing, even when they have a small income. With the aid of experts from Brno, Bratislava is now setting up pilot projects for people in greatest need of housing based on the principles of Housing First. “It’s a very long path before we are like Helsinki, where they can aim to eradicate homelessness completely,” Kára muses. “But it’s important to start naming these issues, as that dictates public policy. This is what we, as responsible people, should be doing.”

Compared to Prague, the Bratislava city hall seems much more ready for action in carrying through specific solutions. The Bratislava coalition has a much stronger position, and unlike Prague’s, is unified on issues of housing. The comparison yields one more difference: while in the Czech Republic, similar approaches are often considered left-wing and sometimes even “radical” (whatever that may mean), in Bratislava, they are promoted by centrist and right-wing parties. SPOLU, for instance, Lucia Stasselová’s party, is a political partner of TOP 09, the Czech liberal-conservative party. Prague’s conservatives could learn a thing or two from their Slovak colleagues.

Housing equals living

“Unfortunately, Czechoslovakia and the entire Eastern Bloc was unlucky in having an ideological rupture in a period when neoliberalism was already the dominant ideology around the world,” says Elena Szolgayová, placing today’s problems in context. More and more experts, such as sociologist Saskia Sassen, draw attention to the fact that as far as housing goes, neoliberalism simply does not work. “The unavailability of housing grows into all sectors of society; it is a factor impacting economic and social life. But it’s hard to trace these connections from a layman’s perspective,” explains Szolgayová. “The neoliberal ideological principles of the 1980s left a huge mark on the first attempts of post-socialist countries at approaching the issue of housing. And it has become apparent that the more liberal a country’s approach was, the greater the problems it has on its hands today.”

“We subordinate our lives to the housing we can afford,” says Michal Janák of the social impact of unavailable housing. I met him in the Nová Cvernovka cultural centre to discuss how the current crisis impacts twenty- and thirty-year-olds. “Many people live with partners they no longer want to be with simply because they cannot afford to live on their own,” he explains. And it’s not just partners: in Slovakia, some 60 per cent of young people live with their parents. The country is the European record holder, tied with Croatia for first place.

Janák, who works as an architect, also draws attention to the part his field can play in formulating societal conditions. The prevailing typology of Slovak apartments reflects the normative idea that the inhabitants of the apartment are a traditional family. “In Austria, for instance, the apartments under construction right now are much more diversified – adapted for the cohabitation of several single individuals, for instance,” he explains, describing the Austrian approach as more democratic.

According to Janák, the problem of market mechanisms is that they narrow the issue down to the greatest common societal denominator, which can also make the most money. “Today, people over thirty opt for a particular way of life just to have a roof above their heads, and this seems dangerous to me.” His words are a stark contrast to the political slogans that so favour the happy – of course, most often also the “traditional” – family. Perhaps they will also once come to the realisation that even a happy family has to have a dignified place to live.

English translation: Ian Mikyska